- Executive Summary

- Introduction

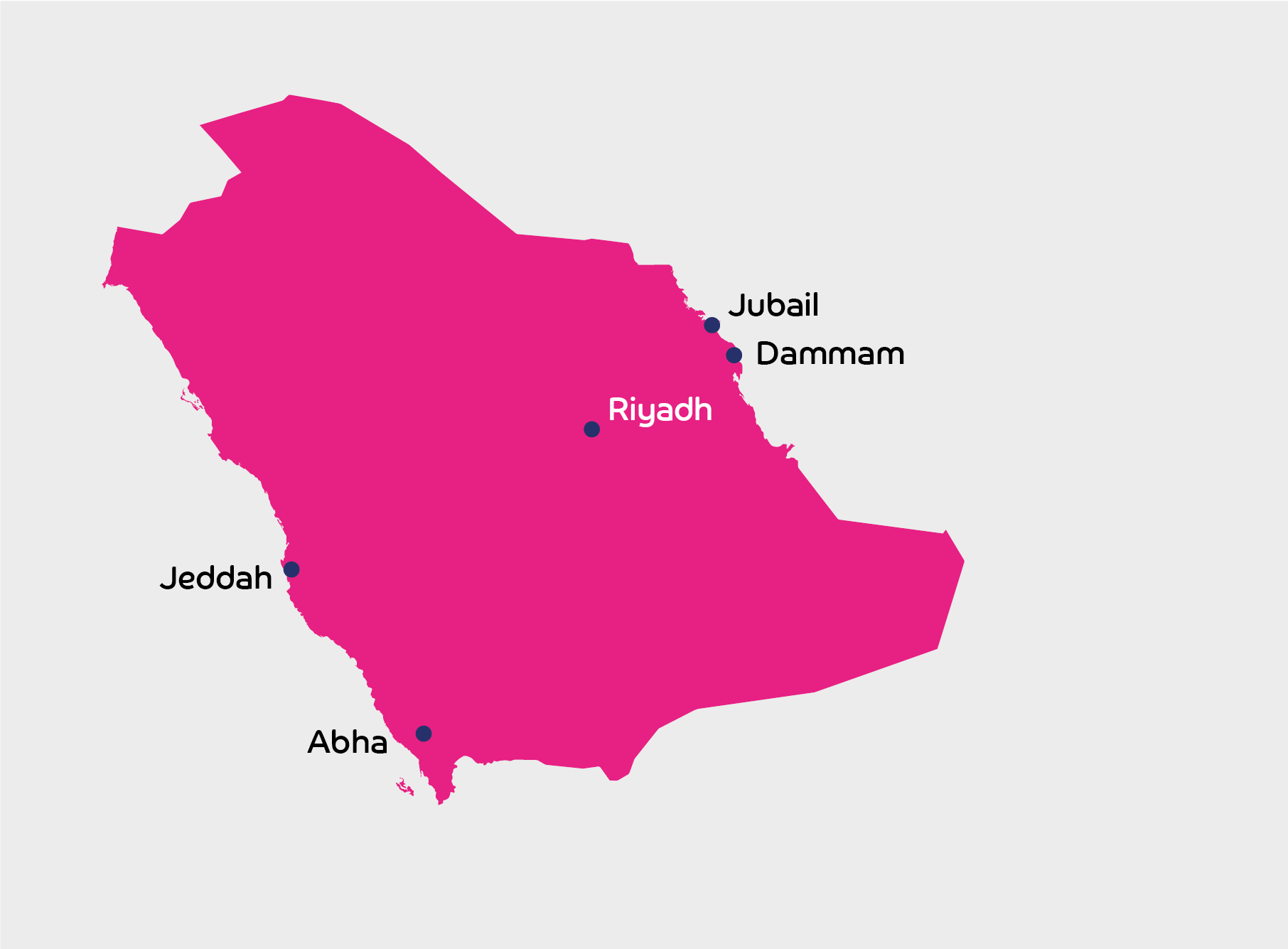

- The impact of COVID-19 on migrant workers in Saudi Arabia

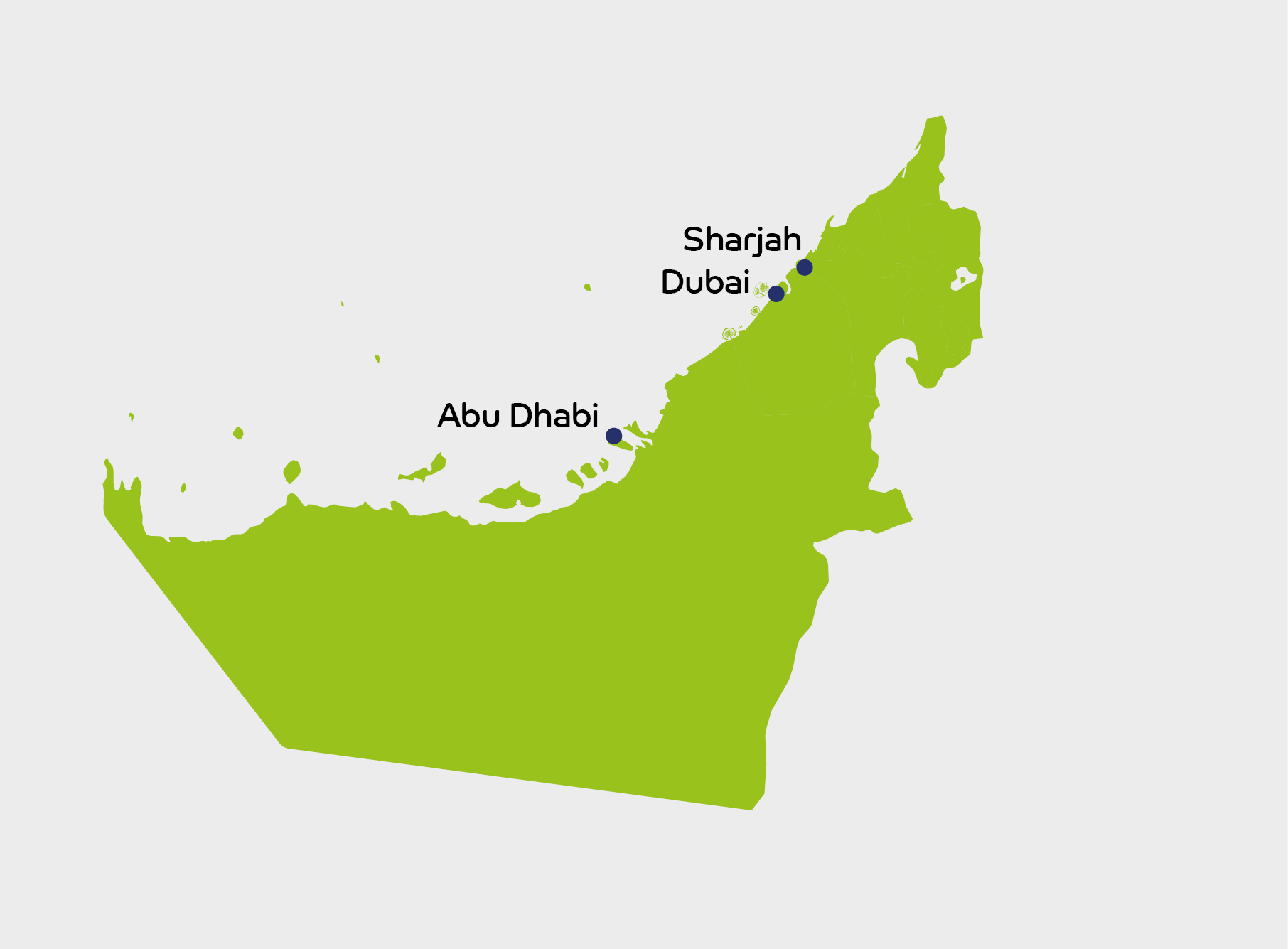

- The impact of COVID-19 on migrant workers in the United Arab Emirates

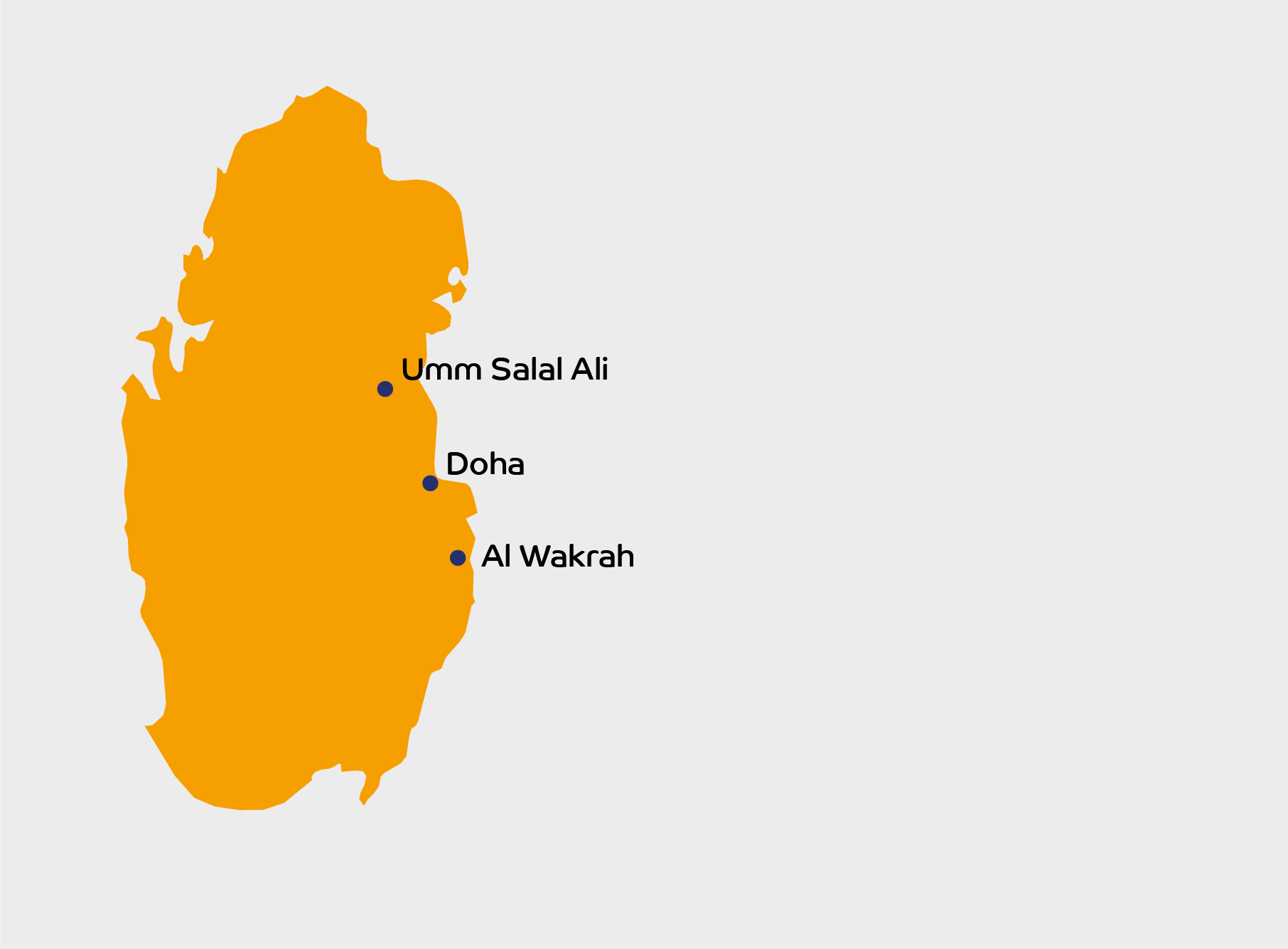

- The impact of COVID-19 on migrant workers in Qatar

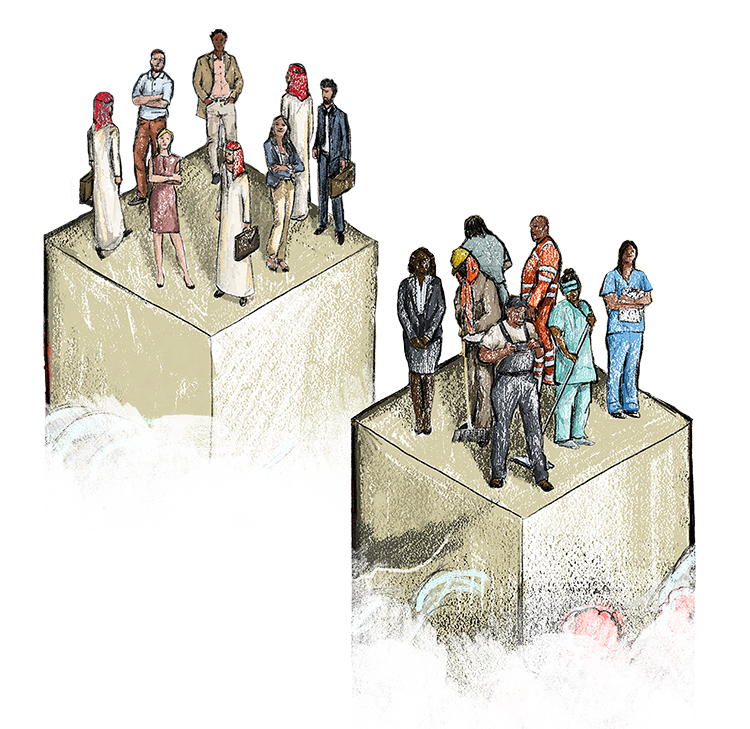

- Migrant workers and racial discrimination

- Business responsibilities under international human rights standards

- Looking forward – A new normal?

The Cost of Contagion

Executive Summary

The 2020 G20 will aim to build and enhance a policy framework conducive to empowering people and creating economic opportunities.

“Empowering People”, G20 Summit statement from the Saudi Arabia Government

Nobody knows the extent of the mental toll this situation has put on us. There is a very real chance that many workers will resort to suicide. The Government should do something for us. It’s either that or they’ll have to send our dead bodies home. [0.1]

Bilal, construction worker in Dubai, United Arab Emirates

In November, world leaders from government and business will gather at the G20 Summit hosted by Saudi Arabia. A statement on the Summit released by the Saudi Arabia government speaks of “Empowering People” and addressing a global economy that “is not delivering for all” and as “inequalities are growing amidst a rapidly evolving environment.” The ongoing global coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic will undoubtedly be a major topic for discussion. Under its presidency of the G20 this year, Saudi Arabia promises to “focus on policies that promote the equality of opportunities especially for underserved groups.” [0.2]

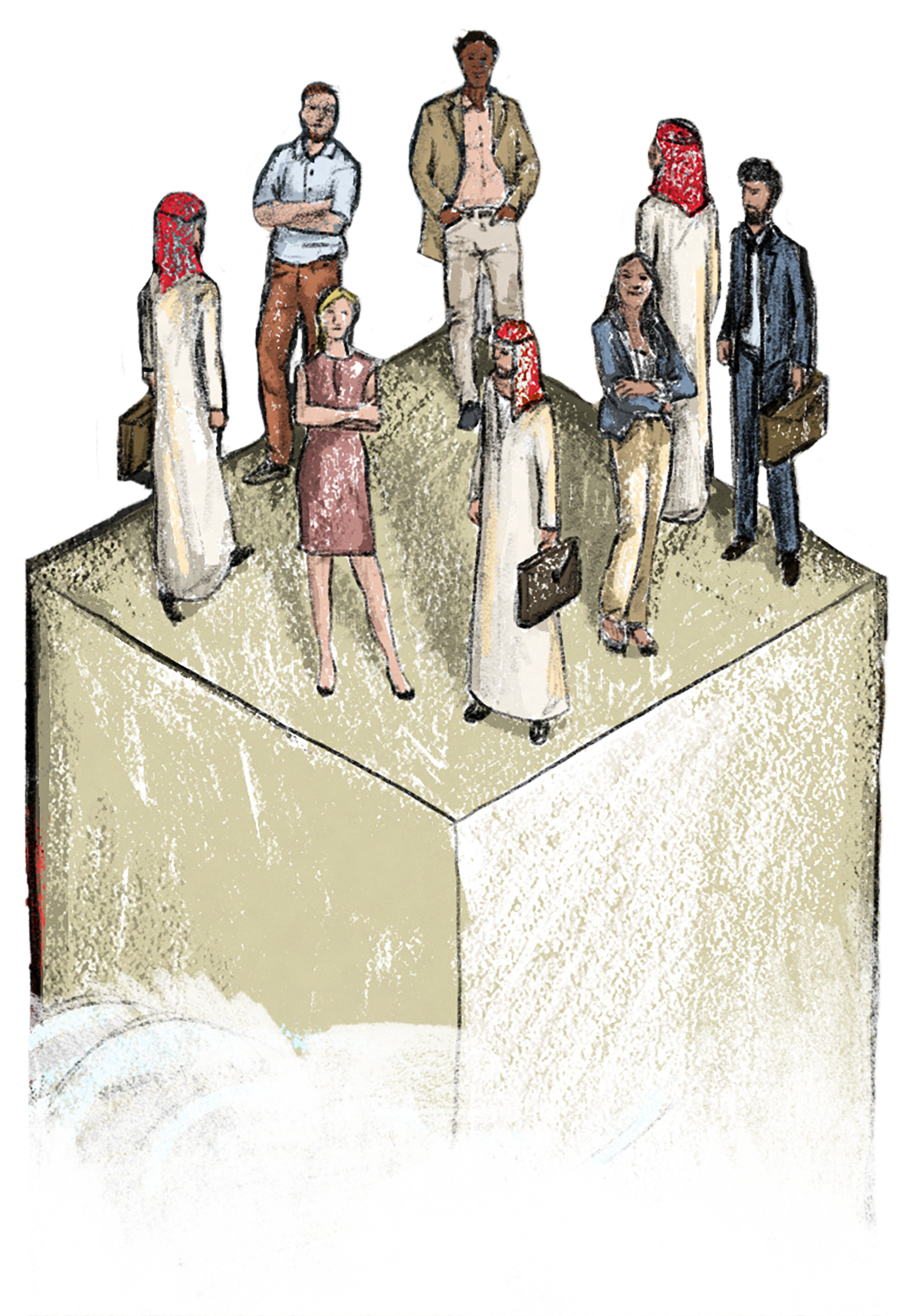

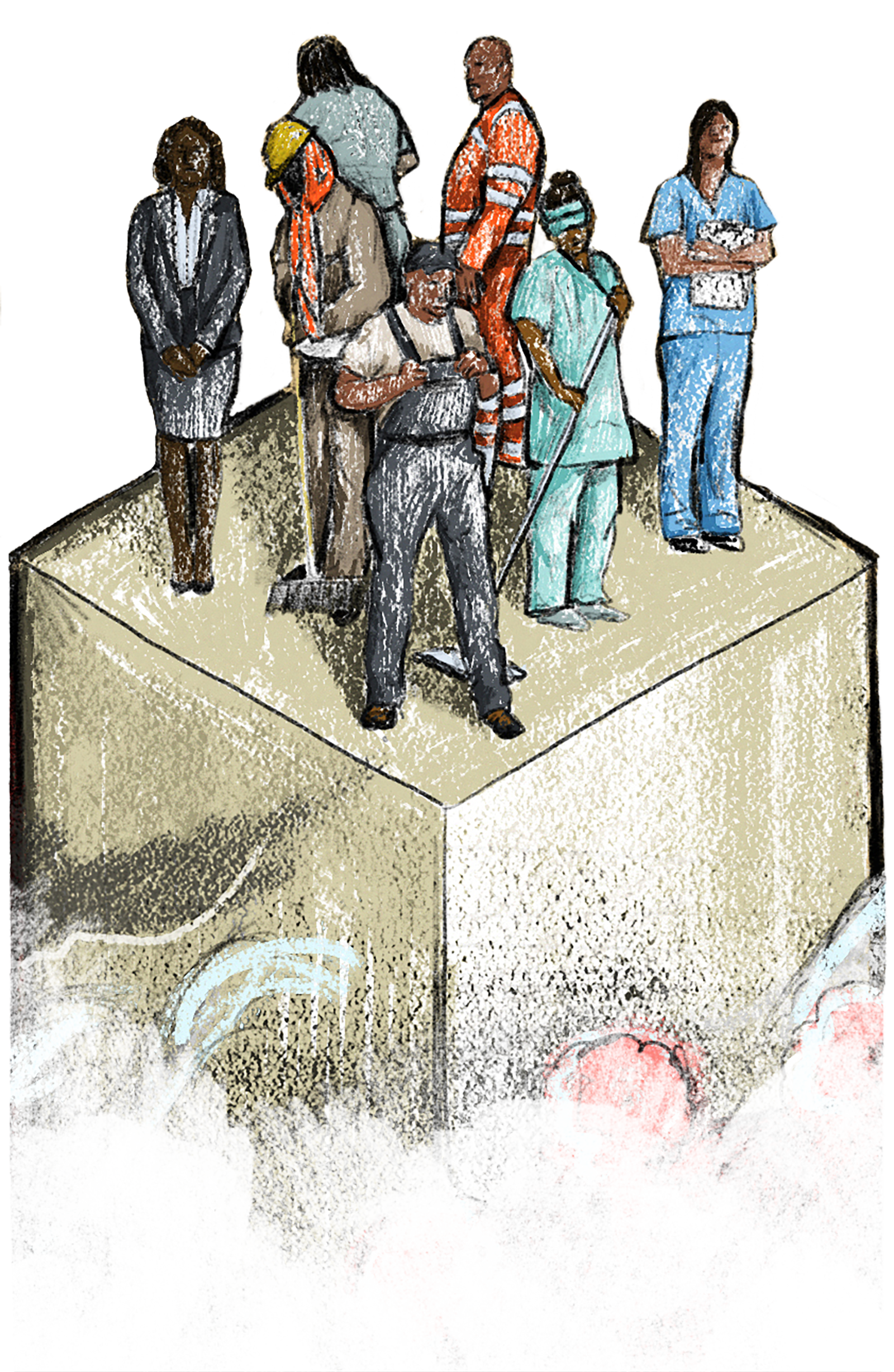

As this report documents, the ground reality is very different from these noble aspirations. Governments and businesses in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and, to a lesser extent in Qatar, have been guilty of racial discrimination in their response to the COVID-19 pandemic, acting quickly to provide financial and other benefits to local business and nationals, while leaving thousands of migrant workers in jobless destitution and, in some instances, facing death, and the ever-present risk of being infected by a deadly virus.

Migrant workers left destitute by reduced and unpaid wages

Equidem’s research uncovered cases of unpaid wages and other exploitation that cut across sectors and businesses big and small. Companies have placed migrant workers on drastically reduced salaries or unpaid leave without their consent and inadequate monitoring by state authorities. Even some of the largest businesses in the region are guilty of practices that amount to discrimination, modern slavery or labour exploitation with regard to workers in their supply chains. For example, Saudi Aramco, the giant Saudi oil and gas conglomerate, the second-largest company in the world, appears to have maintained wage payments for its own low-wage employees. However, our research reveals that thousands of low-wage migrant workers employed by subcontractors were left unpaid for as many six months. This has left workers in Aramco’s supply chain in situations of poverty and extreme distress.

Saudi Aramco

Equidem spoke to fifteen migrant workers employed by six different subcontractors of Saudi Aramco. The men said their companies failed to pay them either wages owed before the pandemic struck Saudi Arabia, during the pandemic or both.“I had heard about a policy of the Saudi government according to which the employer has to pay 60% of salary up to 6 months to those not having work,” said Rabindra, who works at the North Terminal of Saudi Aramco, Dammam who is employed for M.S. Al-Suwaidi Holding Co. Ltd, a sub-contractor of Aramco. He added, “but my employer has not paid me since March. We were told that we will be paid 50% of our salary, but we haven’t received anything yet.” [0.3]

Migrant workers on a crude oil pipeline upgrade project for Saudi Aramco. They told Equidem that their employer, an Aramco sub-contractor, terminated their contracts after the COVID-19 pandemic started. The men say they are owed wages and their end of service benefit payments. © Equidem 2020.

Dubai Expo

Thousands of workers employed by construction companies working on the Dubai Expo mega project in the United Arab Emirates have lost jobs with little or no notice and with salaries and benefits for work already undertaken yet to be paid. Many of these workers were put on a plane and sent home, while others languish in basic, crowded worker accommodation camps without pay and far from their families. Equidem documented nine cases of workers employed by four separate contractors operating on the Dubai Expo who had not been paid wages. Govinda, a construction worker employed by JML (UAE) LLC on the Dubai Expo mega project, told Equidem that the 300 AED ($80) he received from his employer every month to cover food expenses during the pandemic was insufficient, particularly as he has not received a salary since the start of the year. On top of that, JML said the food allowance would be deducted from his salary once he started working again:

Now that the work has also started, and we do 10-15 days’ shift in a month, we thought we would get our payment. But, we still have not got our salary. The company always tells us to have patience and we will get paid, but no one knows when we will be paid. All of us are struggling financially. We have responsibilities on our shoulders. Who will take care of our family if we are not paid? [0.4]

FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022™

Even workers employed by a sub-contractor on construction sites for the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar were subjected to exploitation and physical abuse. At least one worker employed by a World Cup site sub-contractor died of complications after he tested positive to coronavirus and waited days to be shifted to medical facilities. Rifat, a construction worker employed by Rise and Shine Group, a Qatar 2022 sub-contractor, said that his friend who was infected with COVID-19 was not isolated and was taken to the hospital four days after testing positive:

"My friend Vyom had high fever for four days. We informed the company about his health but he remained in our camp and was not isolated. He was taken to hospital only after four days. He died at a hospital while undergoing treatment. Our camp boss told us that he was diabetic and had breathing complications that caused his death."

Pandemic changes to labour regime open the door to modern slavery

These practices have only been possible because the Governments of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar weakened labour protections and then failed to adequately enforce laws and programmes on wage payments. This made it easier for employers to reduce salaries or terminate employment contracts, leaving thousands of workers in situations of forced labour and modern slavery virtually overnight. Equidem documented several cases of workers being made to sign documents against their will that enabled employers to claim low-wage staff had volunteered to take pay cuts or go unpaid. Some of the workers interviewed by Equidem said that they feared reprisals for complaining about lack of payments from their employer. Parth, a construction worker in Saudi Arabia, said he and other co-workers had not been paid for five months. He told Equidem:

When we ask for our payment, we get beaten up. This is not the first-time workers at the company have faced physical abuse. They make us work overtime duty hours without paying for the extra hours. Anyone who refuses to work is beaten. Many workers have already run away from the company. A worker in the company, told me he was beaten up by the supervisor a lot. We are all scared to file a complaint because then, we will get beaten more. I just want to get my payment and go home. [0.5]

Crowded accommodation camps and poor quarantine facilities increase COVID-19 risks

Even where governments have acted to improve conditions in migrant accommodation camps or at their places of employment to prevent the spread of the virus, this has not adequately raised standards to protect migrant workers. Whether in their accommodation or at quarantine facilities, workers continue to be placed in situations where social distancing is simply impossible. “There are 3,000 workers in the camp where I live,” said Govinda a painter employed by JML Constructions, a Dubai Expo contractor in the United Arab Emirates. He added, “each floor has a kitchen and toilet and around 80 people share a single toilet and kitchen. It gets very crowded. In the morning there are lines to use the bathroom. There is no way we can maintain social distance in such a small area.” [0.6]

Women and men held in separate quarantine facilities in Um Salal Ali, Qatar, after testing positive to COVID-19 complained that it was impossible to socially distance. They also complained about the quality and quantity of food provided. © Equidem 2020.

Severe psychosocial impacts of the pandemic on migrant workers

Dozens of migrant workers told Equidem they were dealing with significant insecurity and stress as they are struggling to survive financially and deal with the risk posed by COVID-19 to their health and ability to earn a living. Bilal, a construction worker in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, said:

This has led us to panic. I am afraid and have depression as well. Nobody knows the extent of the mental toll this situation has put on us. There is a very real chance that many workers will resort to suicide. The Government should do something for us. It’s either that or they’ll have to send our dead bodies home. [0.7]

Arnav, working as a sewing machine operator in the United Arab Emirates, said:

All I could think about was my family. I did not have money to send them. Every bite of food I took here, I remembered my family. It pained me knowing that they are struggling to buy food. We have no farmlands like other people in the village. We have no other source of income. [0.8]

Aarul, a cleaner from Bangladesh working in Doha, Qatar, was left hungry and in total despair because his employer was failing to provide him with wages or food:

I haven’t received my salary since March. We do not get food allowance either. Now we have to wait on the charities to get food, and sometimes we collect enough money to buy some basic items to cook. Some nights I go to bed hungry. Our employer was also supposed to pay house rent but they do not pay it regularly. I came here to work for my family, not to be a beggar living on my own. [0.9]

Gulf government initiatives to protect migrant worker wages and health

All three governments have set up schemes to protect wages and enable access to health care that would provide the basis for a rights-respecting response to the pandemic if adequately implemented. Among these responses are several good practice and positive policy initiatives, including:

- The provision of free health care services to all migrant workers irrespective of their legal status in the country with the guarantee that irregular workers can access this care without fear of any penalty.

- Guaranteeing the full salaries of migrant workers who are in quarantine or undergoing treatment for COVID-19.

- Ensuring that stranded migrant workers have access to adequate accommodation and food while in lockdown.

- Developing national, multimedia information campaigns in different languages that are specifically aimed at migrant workers.

- Establishing multilingual hotlines for accessing information and making complaints against companies that are not complying with the law.

- Free visa extensions and refunds for those impacted by the crisis.

Significant non-compliance by businesses across industries

Our research indicates that there is a significant level of non-compliance by employers with many of these initiatives and other regulations. The fact that government authorities in the Gulf are prepared to commit to policies like providing free health care to migrant workers, on an equal basis with its citizens, regardless of race, gender, ethnicity, nationality or residency status, is a positive advance. So too is Qatar’s stated ambition that many of the measures introduced to support and protect migrant workers as part of its efforts to combat COVID-19 “will lead to permanent changes that have a positive effect on the society as a whole”. Promises of a reform to the kafala system in Saudi Arabia from March 2021, particularly steps towards the elimination of the exit permit and increased internal labour market mobility, are welcome. If these changes were to be enacted into law and adequately implemented consistent with international conventions and standards, they could lead to a significant improvement in rights compliance in the Qatar and Saudi labour markets. However, even these changes cannot address the significant gaps in protecting the human rights of millions of migrant workers in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar.

Prohibition on union participation hampers labour protections

The inability to respect the right of migrant workers to form and join a union, and collectively bargain, means that a critical ingredient to resolving labour disputes and developing a mature, rights-compliant labour market is absent. Given the scale of the migrant worker populations, an estimated 24 million in the three countries combined, state authorities and businesses alone will continue to struggle with labour disputes involving dozens, hundreds and even thousands of workers at a time. Equidem’s research uncovered serious situations of racial discrimination and labour exploitation. But the most common violations faced by migrant workers are centred around the payment of wages and other benefits. As the international labour system recognizes, these issues are best resolved through a tripartite process that includes worker representation through trade unions. Moreover, trade union bodies are already active in one shape or form in many of the Gulf states, including Qatar and Saudi Arabia.

Path to citizenship key to respecting migrant workers rights

A path to citizenship through naturalisation is also critical to ensuring that the women and men who toil in arduous and often back-breaking low-wage jobs are fully recognized as members of wider Gulf societies. Naturalisation would not only enable the state to codify and implement rights protections into law and practice more effectively. As Gulf authorities recognize the need to shift their economies away from a dependence on the oil and gas industries, naturalisation would help grow and diversify the labour market along with the economy. Most importantly, only naturalisation can address the wide gap between the rights and protections afforded to non-nationals and nationals. States must respect their human rights obligations to all women, men and children regardless of their nationality or circumstances. But a path to citizenship would reflect the de facto reality: that for thousands of migrant women, men and children who have lived there for years if not decades, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, or the United Arab Emirates is their home.

1.1 Recommendations

Recommendations for the governments of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar

Equidem calls on the governments of Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates and businesses operating in these countries to take the following steps.

End racial discrimination

- End the racial discrimination of migrant workers by providing employment, health and other protections and benefits to all women, men, and children without distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, colour, descent, national or ethnic origin, gender or sexuality.

- The authorities should amend labour laws, rules and guidelines in line with their international obligations to prevent racial and other forms of discrimination.

- Address wage discrimination based on nationality by ensuring migrant workers are paid equal pay for equal work regardless of their race, colour, descent, national or ethnic origin, gender or sexuality.

- Ensure migrant workers have non-discriminatory access to health care and other social services regardless of their visa status. Remove the sponsor/employer from the process of registering workers for residency permits, public health and other services.

Pay workers outstanding wages and protect their well being

- Ensure all migrant workers are paid the wages and other benefits owed to them, including the women and men who are no longer based in the country.

- Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates authorities should establish a mechanism to enable workers in the Gulf and in their countries of origin to submit wage and other labour complaints.

- The mechanism should also address cases where workers have died or have been incapacitated so that their dependents may receive any award of wages or other benefits.

- The mechanism should be established in collaboration with businesses and business representative bodies, governments in workers’ countries of origin, international trade union bodies, and civil society groups.

- Actively penalise business enterprises and prosecute business owners, management, and staff who are responsible for unpaid wages, or subjecting migrant workers to forced labour, modern slavery, physical and mental abuse, or other forms of labour exploitation.

-

Establish a mandatory state pension fund for all workers irrespective of their nationality funded by state and employer contributions.

-

Amend labour laws to require employers to pay workers for periods of absence due to illness.

-

Enhance and enforce existing labour protections and other laws that would enable governments and businesses to respect migrant worker rights if adequately implemented.

-

Enhance and enforce existing laws that prohibit the charging of recruitment-related costs to migrant workers.

-

Establish and implement a state-run wage protection and insurance scheme to indemnify wage payments and provide humanitarian support.

-

Work with international and local experts and migrant community groups to develop and implement strategies to provide culturally appropriate and gender-sensitive psychosocial support to migrant workers.

-

Increase worker awareness of their rights and pandemic health care

- Increase efforts to raise worker awareness of their rights and avenues for support and redress, including with respect to labour disputes and access to health care.

-

Enhance and enforce existing requirements on business to conduct mandatory training of migrant workers, ensuring this training is culturally appropriate and gender-sensitive, and conducted in languages understood by workers.

-

Work with migrant community groups, international trade union bodies, and others across a range of platforms, including social and traditional media, to develop worker awareness initiatives tailored to the needs of individual migrant worker groups, taking into consideration the challenges that may be faced by particular individuals and groups based on their nationality, gender, sexuality or other characteristics, and the sectors and size of businesses they are employed in.

-

Respect the right to freedom of association

- Recognise migrant workers’ right to join and form a trade union and collectively bargain through the passage of legislation.

- Work with international trade union bodies and relevant international non-government organisations, and experts to develop legislation and programmes, such as worker representative committees, that assist workers and businesses to transition workplaces that respect and recognize trade unionism.

-

Permit independent human rights and labour rights observers access to Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates to monitor conditions for migrant workers and ensure both observers and workers do not face reprisals for documenting situations of exploitation.

Provide a path to citizenship

- Pass legislation to provide long-term migrant workers with a path to seek permanent residency and citizenship if they so choose.

- Undertake awareness-raising campaigns across a range of platforms and avenues, including through social and traditional media, targeting negative and discriminatory perceptions of migrant workers.

Develop a National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights

- Draft a National Action Plan on Human Rights that includes business and human rights requirements, in line with the provisions of the UNGPs.

- Develop and carry out a plan for the implementation of the UNGPs that includes a strategy for increasing public awareness of international standards on business and human rights. Ensure that the widest possible representation of civil society, human and labour rights experts, and the business community is consulted on an ongoing basis for the development and implementation of state policies on business and human rights.

1.2 Recommendations for businesses operating in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar

To the Business Community in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar.

- Publicly commit to respecting human rights and labour rights and put in place adequate and transparent mechanisms to identify and prevent abuses due to business activities across the business and in supply chains.

- Review business practices and policies to ensure that the company does not commit or materially assist in the commission of acts that lead to human rights or labour rights abuses.

- Require full disclosure from all partners, clients and suppliers, and publish a list of all contractors, suppliers and companies in value chains.

- Seek expert guidance, including that of civil society, to embed the UNGPs and other relevant international standards across business activities.

- Ensure workers are able to exercise their right to freedom of association, right to organise, engage in collective bargaining and collective representation, and freedom of speech.

- Actively develop and encourage industry bodies that seek to advance and implement international standards on business and human rights.

To International Businesses and Investors in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar.

- Develop and implement policies and practices on business and human rights in line with the UNGPs and other relevant international standards that partners and contractors in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar must respect as a legal requirement for doing business with you.

- Share specialist knowledge and expertise on business and human rights with counterparts and partners in the Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar business communities.

- Seek expert guidance, including that of civil society, on how to identify, prevent and mitigate human rights risks due to business activities in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar.

Introduction 1

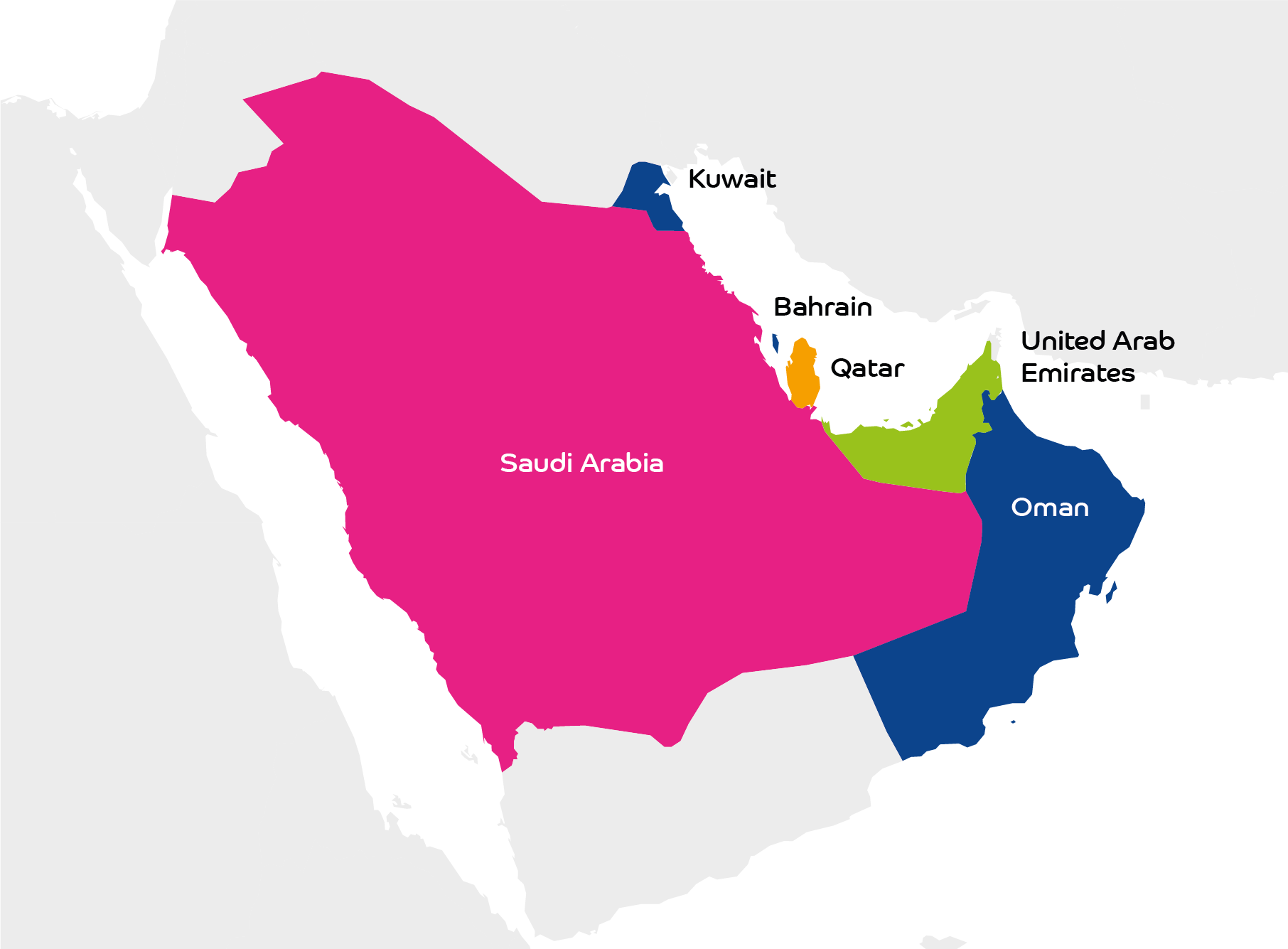

In 2019, the Population Division of the United Nations (UN) Department of Economic Affairs estimated that there were 35 million international migrant workers in Jordan, Lebanon and the six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, and that nearly a third of them were women. [1.1] Migrant workers in the GCC States of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain and Oman account for over 10% of all migrants globally and primarily come from Nepal, India, Bangladesh, Kenya and the Philippines. [1.2]Migrant workers make up an average of 70 % of the employed population in GCC countries, ranging from 56 to 93% for individual States[1.3] and are intrinsic to the Gulf’s $1.6 trillion economy.[1.4]These women and men from abroad drive the domestic service sector of GCC economies and have been essential to the development of infrastructure projects and the plans to host the G20 in Saudi Arabia in November 2020, Expo2020 in the UAE (now delayed until 2021) and the World Cup in Qatar (2022).

Migrant worker populations

|

Country |

Total Population |

Migrant Population |

|---|---|---|

|

Qatar "[1.5] |

2,444,174 |

2,160,650 (88.4%) |

|

Saudi Arabia [1.6] |

34,173,498 |

13,088,450 (38.3%) |

|

United Arab Emirates [1.7] |

9,992,083 |

8,783,041 (87.9%) |

Equally important is the role migrant workers play in supporting the economies in their countries of origin through the money they transfer back every month to their families. In 2017, migrants in the Arab States remitted over $124 billion to their home countries. [1.8]Despite the contribution that migrant workers make to Gulf countries, they are generally undervalued and there are regular reports of individuals being subjected to human and labour rights violations. These include: the confiscation of identity documents; contract substitution; extremely long working hours; non-payment/late payment of wages; illegal deductions from wages; unsafe working conditions; overcrowded and sub-standard accommodation; verbal or physical threats and abuse; restrictions on their freedom of movement; and forced labour.

Although most countries of origin prohibit the practice of charging migrant workers for the cost of their recruitment, [1.9] most workers must pay agents or sub-agents to obtain work in the Gulf. [1.10] Many migrant workers take loans to pay the expenses involved in securing a job abroad - such as for the costs of the journey, visas, recruitment fees, and mandatory medical testing – that their employer in the Gulf should incur. Workers can take months or years to repay these debts. Retaining their job is therefore imperative so that they can pay off their debts and support their families, which often makes them reluctant to challenge contract violations.

The legal framework governing the employment and residency of migrant workers in GCC countries also contributes to their vulnerability to exploitation by unscrupulous employers and recruitment agents. For example, all Gulf countries use versions of the kafala system through which a migrant worker is tied to the employer who sponsors their work visa. The migrant’s right to be in the country is thereby dependent on their continued employment with the individual employer who sponsors them, although Qatar has taken significant steps to remove these restrictions. The UAE allows a migrant worker to transfer to a new employer and be issued a new work permit without the permission of their current employer in certain circumstances. [1.11] In Saudi Arabia, a migrant worker cannot leave their job without the express permission of their employer without risking arrest, detention and deportation. ‘Absconding’ from an employer remains a criminal offence in Saudi Arabia and the UAE, and is a powerful coercive tool used to silence workers who might otherwise seek to escape situations of exploitation. Qatar continues to impose harsh penalties for 'absconding' when a migrant worker leaves their employer without permission or remains in the country beyond the grace period allowed after their residence permit expires or is revoked.[1.12]According to Saudi Labour law, if a worker is absent from work for a specific period of time, an employer has to declare them ‘haroob’.[1.13]In UAE, if the worker absents himself without lawful excuse for more than 20 intermittent days or for more than 7 successive days during one year[1.14], the employer can report such worker as ‘absconding’.

End of service benefit

Under the labour laws of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar, workers are entitled to an end of service benefit, a payment that is meant to amount to the equivalent of a certain period of wages for each full year of contracted work undertaken.[1.15]This is a major source of funds for workers nearing the end of their employment with a company. The end of service benefit is a major motivating factor for workers to continue to work without pay, or remain in the country in the hope of eventually receiving the payment. This gives employers significant leverage over workers who would otherwise leave situations of labour exploitation.

|

Country |

Infections |

Deaths |

|

Qatar[1.16] |

134,433 |

233 |

|

Saudi Arabia[1.17] |

351,455 |

5,576 |

|

United Arab Emirates[1.18] |

144,385 |

518 |

1.1 Methodology

This report is based on 206 semi-structured interviews with low-wage migrant workers in Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, India, Nepal and Pakistan between February and October 2020. Interviews were also carried out with migrant worker families, communities, business owners and operators, government officials and other individuals. Migrant worker interviews were carried out on a one-to-one basis in-person and remotely over the phone in line with social distancing and other COVID-19 guidelines set by authorities in these countries and the World Health Organization. Women and men working in low-wage jobs in the Gulf live in an environment of high surveillance, little privacy, and significant physical and mental stress. In light of this, all interviews were conducted with the informed consent of the participants in private locations to respect confidentiality in line with Equidem’s duty of care policy and procedures. Most of the workers interviewed requested that their identity is not revealed. We have therefore decided to use pseudonyms for all the women and men whose cases are documented in this report to protect their identity and shield them against the risk of reprisals from their employers or the state for speaking out. Equidem also consulted other sources of information including laws and other state legal instruments, orders, and guidelines, United Nations special rapporteur reports and statements, and other independent human rights research, international and local media reports, and other secondary sources.

The cases documented by Equidem were shared with the governments of Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, however only the Qatar government sent a detailed response. Equidem also attempted to share all of the cases it documented with the 39 companies identified as being their employer and received responses from 7 of these companies. The responses from these companies are available on our website and are noted below. Equidem would like to thank the authorities in Qatar and the United Arab Emirates and the companies that responded to our requests for help on specific worker cases. Unfortunately, we did not receive a response from the Saudi Arabia authorities, nor from most of the companies contacted.

Time constraints for conducting this research and the difficulty in accessing migrant workers in these countries (due to restrictions on freedom of movement and workers’ reluctance to speak out because of a fear of the employers or the authorities and losing their jobs) mean that the views of some of the most vulnerable migrant workers (e.g. the undocumented, self-employed, daily wage earners, domestic workers, women and other victims of gender-based harm) are largely absent from the report. This is important as these groups are likely to have been the worst affected by the crisis. For example, migrant domestic workers are likely to face significantly increased workloads with schools closed and more members of the household to look after for longer in the day. In addition, their isolation will be further increased as they will be unable to leave the house during breaks or on days off and thereby will find it even more difficult to contact friends or seek other forms of support if they are having problems at work.

All currency amounts in this report have been converted into US dollars unless otherwise specified.

|

Country |

Workers interviewed |

Male workers interviewed |

Female workers interviewed |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Qatar |

90 |

87 | 3 |

|

UAE |

58 | 57 | 1 |

|

Saudi Arabia |

55 | 47 | 8 |

|

Total |

206 | 194 | 12 |

|

Country of Destination |

Country of Origin |

Male |

Female |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bangladesh |

Philippines |

India |

Kenya |

Nepal |

Pakistan |

|||

|

Qatar |

11 |

2 | 23 | 7 | 50 | 0 | 90 | 3 |

|

Saudi Arabia |

5 | 0 | 39 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 47 | 8 |

|

UAE |

3 | 0 | 45 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 57 | 1 |

|

Total |

19 | 2 | 107 | 8 | 60 | 10 | 194 | 12 |

The impact of COVID-19 on migrant workers in Saudi Arabia 2

2.1 Background

Saudi Arabia hosts the third biggest migrant population in the world. Foreign workers account for about a third of Saudi Arabia’s 30 million population and more than 80% of the kingdom’s private-sector workforce.[2.1]In 2017, the remittances sent home by these migrants were the third largest in the world.[2.2]Migrant workers in Saudi Arabia are being disproportionately affected by the pandemic, as reflected in a statement made by the Saudi Ministry of Health on 5 May, which noted that foreign workers comprised 76% of new COVID-19 cases in the country[2.3]Saudi Arabia registered its first case of COVID-19 on 13 March 2020, but it had already introduced some lockdown policies before this date, such as closing all schools and other educational establishments on 8 March. These were reinforced in the following week, including measures which effectively closed the country’s borders on 15 March.[2.4]At the time of writing, the rate of infection was still rising rapidly and increased from 42,925 confirmed cases on 12 May to 347,282 cases on 31 October. However, the number of confirmed deaths from the disease are comparatively low, with 5,402 registered as of 31 October.[2.5]

Saudi Arabia’s labour regime continues to be based on the kafala sponsorship system, requiring migrant workers to be sponsored by a national, resident or company registered in the kingdom. Migrant workers must seek permission from their sponsor to leave the country, called an Exit Permit, or change jobs, known as a No Objection Certificate. In November 2020, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development announced plans to reform the labour regime applicable to the private sector. According to information made public by the Ministry, migrant workers would no longer require the permission of their sponsor to leave the country or change employers at the end of her or his employment contract. The reforms are to come into effect on March 14th, 2021.[2.6]

2.2 Loss of employment and income

The Government of Saudi Arabia considers that the consequences of COVID-19 constitute force majeure and is thereby a reason to terminate an employment contract.[2.7]The Government has temporarily suspended the Wage Protection System and introduced a series of financial support measures aimed at protecting the jobs of Saudi nationals that are under threat because of the pandemic, including the following:

- On 2 April 2020, it announced that private sector employers could apply for support to pay up to 50% of Saudi nationals’ wages, subject to limits on salary and other conditions.[2.8]

- On 3 April, it allocated 9 billion riyal ($2.4 billion) for a furlough scheme to cover 60% of Saudi employees’ salaries up to a maximum of 9,000 riyal ($2,400) per employee during a three-month period. Up to 70% of a company’s national workforce may be covered for three months (or all of them if the business has five employees or less), provided that the employer can show they have been badly affected by the crisis.[2.9]

- The Human Resources Development Fund allocated 5.3 billion riyal ($1.4 billion) to support the private sector to employ and train Saudi nationals.[2.10]

None of the above measures extend to migrant workers. A company that has benefited from the furlough programme must pay the wages of all other employees, both Saudi and foreign nationals, during the furlough period.[2.11]However, as noted above, the authorities have not provided financial support for companies to pay the salaries of non-national staff.

In contrast to these measures, on 6 April 2020, the Government issued Ministerial Resolution No. 142906, which allows an employer to agree any of the following measures with an employee for a six-month period:

- For the employee to take a salary reduction in line with a reduction in working hours;

- For the employee to take annual leave;

- For the employee to take unpaid leave.[2.12]

Nineteen of the 55 migrant worker women and men in Saudi Arabia interviewed for this research said they had not been informed about what was happening to their jobs or whether they would be paid during lockdown. None of the interviewees reported having discussed the options set out in Resolution No. 142906 with their employer and agreeing a way forward.

As will be discussed in more detail below, these measures appear to violate Saudi Arabia’s obligations under international human rights law and labour conventions. The non-payment of wages raises concerns about forced labour, particularly for migrant workers who are indebted because of exploitative recruitment fees and the forced dependency of the kafala system. The reduction of wages and delays in payments, especially without advance notification, and abusive working conditions also implicate the right to just and favourable work conditions.

Sameer, a Nepalese national working as a branch supervisor for Basamh Trading Company in Jeddah told Equidem his employer had not discussed the options set out in Resolution No. 142906 or agreed a way forward about his job. “I am not sure when the company will open,” he explained. “I am not sure what will happen to us in that period. Will the company pay us? Will we have jobs? Will we be safe? All the workers have the same question in mind, what will happen next?”[2.13]Aayan, a Bangladeshi national working as a filing clerk at a company in Jeddah called AlSharif Group Holding said that his employer has not informed him nor his colleagues about their salaries. In March, when the laws were changed in response to the pandemic, Aayan was not sure if he would be paid at all. “I am not sure if they will pay us. We have not received any payment since the lockdown started,” he told Equidem.[2.14]

“We heard that the Saudi’s Ministry of Labour asked all companies to cut the salaries of the workers, increase their working hours or lay them off,” said Asad, a driver working for Mansour Al Mosaid Group. He explained that, “our supervisors told us that we should be prepared for a cut of 30% in the salary. A few days later the company told us to sign a letter for the reduction of salary. What choice did I have but to sign it?”[2.15]

A Saudi Aramco site in Al Khobar where migrant workers employed by Bader H. Al-Hussaini & Sons Co. worked. The workers complained of poor living conditions and unpaid wages that are still owed after their contacts were terminated when the pandemic started.

Saudi Aramco failing to ensure subcontractors pay their workers

Equidem spoke to fifteen migrant workers employed by six different subcontractors of Saudi Aramco, the giant Saudi oil and gas conglomerate, the second largest company in the world. The men said their companies failed to pay them either wages owed before the pandemic struck Saudi Arabia, during the pandemic or both. Gagan, an Indian national working as a procurement engineer for a sub-contractor hired by Saudi Aramco told Equidem that the salary of at least 6,000 workers were reduced by 25%. He said, “My salary has been deducted by 25% staring May 2020. The company informed us about the salary cut beforehand. I used to earn 8,500 riyals ($2,266) before May, now I just earn 6,375 riyals ($1,700). There are nearly 6,000 workers in the company itself, who are facing the same issue. It has created a very difficult situation for us financially. I understand that the company is in a difficult position as well. We are all worried here. We are hoping that this situation gets resolved soon.” He added that a thousand workers were fired from the company without providing them the end of service settlements. He told Equidem, “The company fired 1,000 workers of different nationalities. They did not get an end of service settlement that they were owed.”[2.16]

Jatin, an Indian national who used to work as a mechanical supervisor for a sub-contractor on Aramco projects said that he is worried about providing for his family. He told Equidem, “I worked at Saudi Aramco from September 2, 2019 to September 2020. The company said they could not renew my job contract because of the financial crisis the company was in due to COVID-19. The company gave me 2 months’ notice and paid all my salary and benefits. I am searching for a new job now. If the situation was normal, I could easily get a job. But now, the companies are firing their own staff. Who will hire me? How will I provide for my family if I do not get a job?[2.17]

Naksh, an Indian national working as an appliance group foreman at Bader H. Al-Hussaini & Sons Co, a sub-contracting company of Aramco shared his 15 years’ experience with the company, where he said that the company did not pay its workers on time and that his salary from 2017 was still pending. He said, “I am working for a sub-contractor company of Aramco, Bader H. Al-Hussaini & Sons Co. I have been working here for the past 15 years. The company does not pay our salary in time. My salary from December 2017 is still pending till date. This year, they did not pay my August salary. The company always does this. We are fed up with its unexplained delay. We do honest work and we expect to get paid. I want to join another company. That company has already offered me a job, but my current sponsor is not willing to give me NOC. I went to the labour court as well. The Court is not settling the issue because of my language barrier.” He added, “Whenever we are demanding our vacation, they force us to stay by withholding our salary. I have not seen my family in four years. The company owes me vacation money for four years. This is a common practice here. If the company wants us to withdraw our complaint, they hold our salary. Thousands of workers are facing the same issues here.”

Another worker employed by Bader H. Al-Hussaini & Sons Co, a sub-contracting company of Aramco says he is facing a similar situation.

Migrant workers on a crude oil pipeline upgrade project for Saudi Aramco. They told Equidem that their employer, the Aramco sub-contractor, terminated their contracts after the COVID-19 pandemic started. The men say they are owed wages and their end of service benefit payments. © Equidem 2020.

Lakshit, an Indian national working as an instrument technician at Bader H. Al-Hussaini & Sons Co ., a sub-contracting company of Aramco said that the company has been denying him vacation to see his family. Even when he asked to be relieved from the job, they suggested that he get his replacement first. He told Equidem, “I am waiting for my three months’ pending salary. They are still to pay me my 2 month’s (November and December) salary from 2014. I have not got my payment for August 2020 as well. My vacation money and other benefits are also pending. My only wish is to get my pending salary and go home to visit my family. I have not seen them in 8 years. After 2014, the company started irregular payment. They stopped giving us leave to visit our family. My contract clearly states that I get paid 3 months paid vacation every 2 years. I have two children, a wife and my mother waiting for me at home. I miss them every day. I do not know how they are doing in this pandemic period. I am worried about my family and my children’s education and health. I have requested my sponsor many times now, to relieve me from my job, but they are demanding that I find another person to replace my own post. It’s not my duty to find my replacement.[2.18]

Rabindra, a Nepalese national working as an assistant security supervisor at the North Terminal of Aramco, Dammam said his employer, M.S. Al-Suwaidi Holding Co. Ltd, a sub-contractor of Aramco, has not paid him since March. He told Equidem:

I had heard about a policy of the Saudi government according to which the employer has to pay 60% of salary up to 6 months to those not having work. But my employer has not paid me since March. We were told that we will be paid 50% of our salary, but we haven’t received anything yet.[2.19]

Kishor, an Indian national employed by A.S. Alsayed Company and working for Aramco in Jubail, said he did not get paid even though they worked throughout the lockdown period. “Even though I worked throughout the lockdown, I did not get paid. Even the workers who got paid were only paid half salary and they had no choice but to accept that,” he said. He further noted:

Some of my colleagues were fired without any payment. We are asking for our outstanding salary from the company, but the company is turning a deaf ear on us. All of us are worried about our payment. Many of us do not even have money to buy food. There are hundreds of us.[2.20]

Equidem interviewed 7 migrant workers employed by subcontractors of the Saudi Arabian oil and gas conglomerate Aramco who faced similar situations. Jeet, an Indian national working on an Aramco installation, said that workers employed by A.S. Alsayed Company, the Aramco sub-contractor, decided to go on a strike at the end of July after the company did not pay their salary for at least five months. “The workers here haven’t received any salary since February. Company bosses say the company is running at a loss and that’s why they can’t pay us,” he explained. Equidem spoke to Jeet and other workers employed by A.S. Alsayed Company on July 31st, the day of their strike. Jeet told Equidem:

After the lockdown, the company has been continuously firing workers and none of those workers got salary payments or end of service settlement for work already done. Those of us who are here are all working normal working hours, but the company is still not paying us. This is not right. Today [31st July], all of us workers decided to go on a strike. It is the only way we could compel the company to pay us. A.S. Alsayed Company’s and Aramco’s MD came to convince us to not to go on strike. They said everyone will get salary in two days. If we do not get salary then the workers will go on a strike again.[2.21]

A Saudi Aramco oil pipeline upgrade in Saudi Arabia.

An Indian national working for A.S. Alsayed Company at an Aramco site said the workers were given false hope and promises that they will be paid. But the company has still to pay them even though they continued working. Because of this in mid-August the workers decided to go on strike again. The Indian national said, “I did not get my salary in the past 5 months. The company did not pay its workers during the lockdown, although the work at the company is still going on. I am working at Aramco’s site even today. But the company did not pay us. Three days ago, all of us workers declared a strike, then Aramco officials came to convince the workers. Company officials said that salary will be received by Friday, 21 August, but we did not get anything.[2.22]

An Indian national working for A.S. Alsayed Company at an Aramco site in Dammam said:

The company has not paid me since February. Not only me, the company has not paid any of its workers. We were told that we will get all our payment by Friday (August 21), but when we went to ask for our payment, they again said they will pay us Monday. We are all worried about our payment. We all have families to look after. The company should understand what we workers are going through.[2.23]

“I have not received my salary from March to June,“ said Kripal, a welder working for Al-Rashid Company, an Aramco sub-contractor, in Dammam. He explained:

The company fired many workers just for asking their salary, without providing them with any salary or benefit. We had a lot of problems to manage our finances, but we could not say anything. We were afraid they might fire us as well. My boss said the business was losing money. None of the workers have received salary. I have not managed to send any money to my family in the last four months. I barely have any money to buy food.[2.24]

Other workers employed by subcontractors on Aramco sites complained they had not even paid them their salaries for the months prior to the pandemic measures being instituted in March 2020. Ajaya, who was hired by the National Recruitment Company of Saudi Arabia, (NATREC) to work for Aramco, told Equidem:

The company (NATREC) says it is running at a loss and it cannot pay our salaries. I did not get my salary from January. This was months before the lockdown even started. I had no money to buy food. I sleep with half-empty stomach most days. When we went to demand our salary, we got threatened by the company saying, ‘if you speak, you will be sent to jail.’ We tried many times to gather everyone to raise our voice, but the company dismissed us every time. They fired many workers from their job without their rightful salary and end of service settlement.[2.25]

Abdul, who works for Aramco sub-contractor Azmeel Contracting Company, told Equidem:

Azmeel has not paid me since the lockdown. Because of this, I am having a lot of trouble running my expenses. I had to take a loan with my relatives. Now that the work has resumed, I had hoped that we would get paid. We ask the company frequently about our salary, but we have got nothing yet. The company has already fired more than one thousand workers after the lockdown. So far, those workers have not received any payment as well.[2.26]

Equidem shared the cases it documented with Saudi Aramco and all six of the subcontractors who employed the workers. The subcontractors did not respond. In response to our findings, Aramco said: [2.27]

Aramco takes the welfare of its employees very seriously. We are committed to providing a safe and respectful working environment for all our employees, partners and the communities in which we operate, and we investigate claims of any violations of our standards.

Aramco has robust HR and Contracting policies and procedures in place to protect its employees and contractors, including timely and fair payment. Having looked into the points raised and based on our existing HR practices, we are confident that it is unlikely any of the individuals being quoted in the report work directly for Aramco.

We also have a duty to work with our contractors to ensure that anyone who works on Aramco projects is treated fairly and compensated appropriately. With this in mind, our commitment to legal and ethical business practices extends to our entire supply chain through a Supplier Code of Conduct which outlines mandatory policies on environmental, health and safety issues, fair trade practices, ethical sourcing and conflicts of interest.

Aramco’s internal contractual requirements mandate strict compliance with applicable Labor Laws to protect all parties’ interests and rights, including contractor employee’s living and working environments.

Our contracts require high standards of safety, health and environment controls which meet industry best practices. Inspections are conducted regularly on contractors’ camps that fall within Aramco’s operational areas to ensure adherence to HSE measures. We also have in place a strong system that allows contractors to file claims as a result of non-compliance with their contract’s terms and conditions. Through our Supplier Help Desk Center and Supplier Service centers, Aramco is able to provide both remote and in-person support. All calls are tracked and monitored until reported issues are resolved and closed.

Our commitment to upholding the highest standards and maintaining a safe and healthy workplace environment means that we continuously review existing practices. Throughout the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, we acted swiftly by implementing measures across our operations to reduce the risk of the spread of COVID-19 and to mitigate the virus’s impact on our communities and our business. This includes steps to support contractors’ efforts to maintain safe working and living conditions for their employees during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as promoting awareness and wellbeing through training and regular communication with contractors to ensure awareness and adherence to Aramco and applicable government requirements.

Additional information on Aramco’s support efforts and response to COVID-19 can be found in more detail on a dedicated webpage here and an official press release here.

The Saudi Aramco worksite pass of a sub-contracted migrant worker who did not receive wages owed during the height of the pandemic. © Equidem 2020.

Our research indicates that other companies in Saudi Arabia have been using the pandemic conditions and the changes to the labour regime to justify the non-payment of wages to their low-wage migrant worker employees. “In our company, where I work as a driver, our salary has been delayed. We have not received salaries since December 2019 even before the start of COVID-19,” explained Asad. He added, “often we used to get two salaries together. In mid-February, we were expecting to receive our two salaries December and January. But we did not receive it. Then the COVID-19 issue arrived, and we were asked not to come to the company.”[2.28] Shaurya, an Indian national working as a painter for the real estate company Al-Sayyar, said he and his co-workers had not received their salaries for more than two months before the first case of COVID-19 was recorded in Saudi Arabia, making their financial situation even more difficult:

We are not working now. We have not yet received our salary since January [2020]. Even after asking many times, the company does not tell anything about salary, they just say that if the work starts, you will get money. For now, only food will be available.[2.29]

In March, Equidem spoke to Surya, a Nepalese national working as a real estate officer in Al Khobar. Surya said he and his colleagues had not been informed about what was happening to their jobs or whether he would be paid during the lockdown. He said, “my office has not closed yet. It is open for two hours in the morning and one and a half hour in the evening. I will know if the company will pay us only at the end of the month.[2.30]Equidem later learned that Al Khobar did not pay Surya and other low-wage migrant worker staff. Zayed, a Pakistani national working at Shirka Majmua Zayed Al Hassan Construction, expressed anxiety about the future of his employment since he was made to sign a paper that allowed the company to terminate workers’ contracts at any time. “When the COVID-19 crisis started, first they suspended our overtime. Then we received our salary fifteen days late,” Zayed recalled. “The company asked us to sign an agreement, allowing them to lay off workers anytime. So far, they haven’t laid us off. But they haven’t paid us for the time period we did not work. We are not sure what will happen to us.[2.31]

Other workers told Equidem that their company had simply stopped paying them since the lockdown was announced. Babulal, an electrician employed by Alodood Contracting Company, said:

The company said that there will be some delay in the payment of wages. We haven’t received any payments since the lockdown (was announced in March). I have not received my salary for the last 3 months. I am facing a lot of trouble financially. I do not have money to buy food. I had to borrow money from friends to buy some basic things. Even after the work resumed, we did not get any salary. The company has sent many workers back home. They have neither been paid their salary nor other benefits.[2.32]

Workers at Al-Jeraisy Group told Equidem that the company fired them and up to 500 workers without salary or end of service settlement. The workers said the company made each of them sign a letter that was written in Arabic only:

The company fired us workers without paying our salaries and allowances. They told us that the company did not have much work. The company got all the workers to sign on paper, a letter that was in Arabic. I did not understand what was written on the letter. I think it was a resignation letter. Workers are still trapped in the camp without pay. They do not even have money to buy food. It is really a miserable condition.[2.33]

Girish, another worker employed by Al-Jeraisy Group, told Equidem:

None of us received any payment throughout the lockdown. Before firing us, the company had us sign a paper, which was in Arabic. I do not know what was written in the letter. The company owes us a lot of money. Some workers have come home, but a lot of workers are still stuck at the camp due to travel restrictions.[2.34]

Some of the workers interviewed by Equidem said that they feared reprisals for complaining about lack of payments by their employer. Imaran and Parth, who worked for Aswar Aseer Group, were subjected to physical abuse by their supervisors when they asked for their salary. Imaran, who was employed as a truck driver, described his ordeal to Equidem:

I haven’t received my salary for five months. The company is not paying any of its workers. I had regular duty hours, even during lockdown, but I did not get paid. The only payment I got was of 300 riyals ($80), which was for food. The supervisor beat us when we asked for our salary. Some workers ran away to avoid this abusive behaviour. The company fired many workers and has not paid their salary. I too want to go home, but I cannot go without my payment. I do not have money to buy air ticket.[2.35]

Parth, who worked as a labourer with Aswar Aseer Group, said he and other co-workers had not been paid for five months. He said:

When we ask for our payment, we get beaten up. This is not the first time workers at the company have faced physical abuse. They make us work overtime duty hours without paying for the extra hours. Anyone who refuses to work is beaten. Many workers have already run away from the company. A worker in the company, told me he was beaten up by the supervisor a lot. We are all scared to file a complaint because then, we will get beaten more. I just want to get my payment and go home.[2.36]

Workers continue to work during the lockdown but not paid

A feature of cases like this is that workers who continued to work during the lockdown have simply not been receiving salary payments in full. For example, Mitesh, who works for Civil Works Company, said, “I am a cleaner and was working throughout the lockdown period. The company only paid half of my salary. I asked the company for remaining salary, but they did not pay.”[2.37]

An Indian national working as an ambulance driver at a hospital in, Riyadh told Equidem he had not been paid since the lockdown announced in March. He told Equidem, “I am working as an Ambulance Driver the past 2 years. I haven’t received my salary since the lockdown. The company says they will cut the salary and at the same time, these days, we have done 16 hours duty carrying high-risk patients, even though we are worried about our health.”[2.38]

“I worked throughout the lockdown period. The company made us work longer harder hours than before. But when the time came to pay us, they said the company has no money because of coronavirus and business was down. One of the managers said the company had no money to pay me and other workers,” said Yagnesh, an Indian national working for A.S. Alsayed & Partners Contracting Company, an Aramco sub-contractor.[2.39]

Wahab, an Indian national working for the Aramco sub-contractor The National Recruitment Company (Natrec), told the investigators that he had not received payments for the last six months. He said:

I worked throughout the lockdown but did not get paid. The company says that there was a lot of loss in the lockdown, so nobody will get salary. The company is intimidated by demands of salary. Let’s say if you speak more, they will put you in haroob [charged with absconding or runaway, a crime under Saudi law].[2.40]If you leave the company and inform the police about the escape, they will put you in jail. During the lockdown itself, the company fired many workers from their jobs without pay. Many such workers are upset here.[2.41]

Workers made to sign contract termination documents without their consent

Other workers interviewed by Equidem said their employer made them sign documents that they did not understand, that were not explained to them, and which they assumed enabled the company to justify not paying their wages. Qadim, an Indian national working as a steel and glass fixer in the city of Riyadh said his company had forced him to sign a document ending his contract with the company:

On March 16, the owner (of the company) glared at me. He told me to sign a document, he did not explain what it was. After I signed it he said I was terminated. The company discriminated against us. They fired many other workers but did not fire a single Saudi. We did not get any help or money after signing the paper. I neither have money nor accommodation. I am buying food borrowing some money from my friends and relatives. I am living in an old building, which is not built for accommodation purposes. We have to bring water from far away for the building.[2.42]

“Instead of paying me, the company decided it was easier to fire me,” said Rayaan, An Indian national working at Rekaz Al Khaleej in the city of Riyadh. “They made me sign a document stating all my salary and other benefits were paid, but in reality, I did not get a thing. In the name of signing my exit paper, I was robbed of my salary. Now I do not even have money to buy food.”[2.43]

Mitesh, an Indian construction worker with Civil Works Company, said he and many other workers were fired and sent back to their home countries with four months of salaries and end of service benefits unpaid. “Every time we asked about our payment, the company said ‘no one will get salary during this corona period’. Later, they made us sign a paper and said they will call us as soon as the work starts.” But while Mitesh and other workers waited their visas were cancelled and, at least all of the workers who were Indian nationals were put on a plane back to India. “My contract period was up to July 2021, but they sent me back to India anyway. There are thousands of workers in the company who are facing the same problem as me. Only a few workers there still have a job and are still being paid.[2.44]

Rohan, who also worked at Civil Works Company, said the company made all of the workers sign a document without explaining what it was. Afterwards, the workers’ contracts were terminated, and they weren’t paid any of the salary or end of service benefits owed to them:

Us workers are now left without a single riyal. We are asking for money from their friends and family to buy food. They cannot go back home because flights are banned. The company should have at least provided them with food.[2.45]

Rabindra, another worker employed by M.S. Al-Suwaidi Holding Co. Ltd on Aramco’s North Terminal site in Dammam said he and other colleagues were given two choices, either to sign a document saying they agreed to be on an unpaid leave for 6 months or get fired from work. “We haven’t been paid since March. The company suggested us to sign a paper which says, “I am ready to stay in unpaid leave for six months,” he said. According to Rabindra, workers who signed the paper are left to languish in the camp without work or pay. Workers who refuse had their contracts terminated immediately. While they remain in the same camp, the company has refused to confirm whether they will pay salaries on work already completed or an end of service benefit. Rabindra said there were over 400 workers at the camp who were in this situation because they refused to sign the document.[2.46]

Ritesh, who works for Aramco sub-contractor Kass International Contracting Co. Ltd., said he received only 10% of his salary during the lockdown period. He said the company had not been paying their salary on time even before the pandemic. “During the lockdown, I got only 10% of my salary. I have yet to receive 5,000 SAR ($1,300) from the company. They used to pay our salary on time, but it has been 2 years since the company continuously delayed payment. We cannot complain at Aramco even if we do not receive salary since we are outsourced.”[2.47]

Some companies continued to provide food and accommodation during lockdown, but five workers complained that they received nothing and could not afford to eat properly, or that the quality of the food they were given was poor. Asad, a driver from Pakistan with Mansour Al Mosaid Group, told Equidem, “most other workers, including me, have been staying at the accommodation which has been provided by the company. The company pays us 300 Saudi riyals ($80) a month for food. But this is not enough to eat properly, every night I go to bed still hungry.”[2.48] Shaurya, who is employed by Al Sayyar, told Equidem, “this lockdown has messed up our lives. There is a crisis for food. Although we were told that the company will provide us with food, the quality of food is very poor. Food comes in a packet. It smells bad too.”[2.49]

An Indian national working as a welder at Azmeel Contracting Company working on an Aramco site in Dammam told Equidem that he and his colleagues were stranded at the company camp and had not even been paid a food allowance during the lockdown. He said:

The employer has not given any information about the future of our work or payment yet. When I called the manager and ask for help, he neither paid my outstanding salary nor helped me. All the workers of the company are facing the same issue. Like me, the rest of the people can afford to eat only a meal a day.[2.50]

Azmeel workers interviewed by Equidem complained that their employer was failing to meet the minimum standards set by the Saudi government for the payment of wages and food allowance, leaving them destitute and hungry. Tejas, who works as a welder on an Aramco site for Azmeel said:

I was managing my life with what little I had, but due to the lockdown, my whole world has turned upside down. My family and I are going through a lot of hardship. I do not have money to buy food. It has been months that I’ve just been eating some vegetables every meal. I can only afford to eat once a day. I make lentils and buy two loaves for one Saudi riyal ($0.30). This is what I eat in a day. This is all I can afford.[2.51]

Other companies simply left workers to fend for themselves and did not provide any food or food allowance. Viraj, who works for International Recruitment Company, Jeddah, an Aramco sub-contractor, said that he had to seek housing and food from his personal support network because his employer stopped paying him and did not provide him with food:

My company did not pay my outstanding salary and other payments when I was fired. I was penniless after the lockdown. Many of my friends also did not receive their end of service settlement. I called the company office several times but each time they refused to pay me. They did not even provide us food. I had to take a loan from my relative and arrange for food. I have gone to bed many nights hungry. Right now I am staying with a relative. They are taking care of me. I would have died if my friends and relatives had not helped me.[2.52]

Workers from other companies spoke of facing similar ordeals. Qadim, a steel and glass fitter from India, said, “it was very hard for me during the lockdown. I had no job and no money. I was starving. I went without food for several days in a row. My employer did not help me at all.”[2.53]

Migrant workers back at home

Those migrant workers who were outside Saudi Arabia when the lockdown began have not been able to enter the country and have lost their only source of income. Others have been unable to return home and have been stranded in Saudi Arabia without support.

A Bangladeshi national working as a chef at Al-Ariad Sweet Corner, Riyadh said that his employer had unilaterally terminated contracts of colleagues who had returned to Bangladesh on annual leave. He told Equidem, “Fifty to 60 workers who had gone home on their annual leave are not able to come back. There are four Bangladeshis in the group. They are my friends. It is sad to see them in a situation like this. They will not be paid. The greatest financial impact will be on their daily life. They need money to buy their daily needs, which is not available without work. Since they are not allowed back in the country, they have no choice. It will be very difficult to manage expenses without a source of income. They might even have to take a loan, probably at a high interest rate, considering the present situation of COVID-19.[2.54]

A Nepalese national employed as an air conditioner technician at Arabian Fal Company in the city of Ras Tanura who had returned to Nepal before the lockdown has not been paid a pending company bonus of 2,300 Saudi riyals ($5,047) for over three months. He told Equidem, “I came to Nepal for my holiday. I was supposed to return to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia on 19 March. I could not go back as all international flights from Nepal were suspended. They say the same ticket will work once this all clears up. My visa period for Saudi Arabia has already expired. I do not know if the company will take me back or not. I want to go back to work. I will try my best to go there again. I am yet to collect Nepalese Rupees (NPR) 500,000 to 600,000 or 2,200-2,300 Saudi Riyal ($4,206 to 5,047) as a bonus from the company.”[2.55]

An Indian national employed as a staff nurse at Eye Specialist Hospital, Dhahran was thirty weeks pregnant when she spoke to Equidem in early May this year. She told Equidem: “I am working as a staff nurse in Saudi Arabia and I am 30 weeks pregnant now. I wanted to go back to Kerala but unfortunately due to this crisis which led to lockdown, I could not go to Kerala. I had booked a flight for 23 May, but it was cancelled. I am stuck in Saudi Arabia in this vulnerable situation. The hospital I work for is an eye specialist hospital and does not have delivery facilities. I am all alone here. I do not have anyone to support me. All my family members are in Kerala. I want to go home so bad. It is a dreadful situation. I am scared something will happen to my baby.”[2.56]

The Government of Saudi Arabia has sought to assist those who are unable either to enter or leave Saudi Arabia during the travel ban by announcing that employees whose Iqama (residency permit) expired prior to 30 June 2020 will have it extended for a period of three months without charge and that fees for new visas which have been unused during the ban will be refunded.[2.57]However, this provision is unlikely to help migrants whose Iqamas ran out before the lockdown because their employer failed to renew them.

Workers living and working in Saudi Arabia with an expired Iqama or who are unable to produce one when requested face criminal penalties. These penalties include fines, detention and even deportation. Three interviewees described how they had been left without a residency permit from before the lockdown. Many of the workers interviewed by Equidem in Saudi Arabia had already been working without a valid Iqama before the pandemic started. Tejas, who worked for the Aramco sub-contractor Azmeel Contracting Company, said:

My Iqama has been over for a year. I requested the company several times, but they did not renew it. About three thousand people from the company live in the camp where I live now (New Camp Sikko Dammam), none of us have Iqama, the date of Iqama ended more than a year ago. The company is not renewing, nor is it sending people home. We are living here like bonded laborers.[2.58]

When employers fail to renew residency permits for their workers it means they cannot access the public health system. This can have serious consequences for workers with health problems, and during a pandemic. Ajaya, who was employed by Natrec, the National Recruitment Company of Saudi Arabia, on an Aramco site, told Equidem:

My Iqama expired 7 months ago. Just a few days ago, I was suffering from high fever. I had no money to go to the hospital. I borrowed 60 riyal ($15) from my friend to buy medicine. Many people got ill during the lockdown. None of them could go to the hospital because their Iqama had expired. The company completely ignores us when we request them to renew our Iqama. There is also a practice of reducing salary for taking sick leave in my company. Apart from the weekly day off, any day that you do not go to work, that day’s wages will be deducted from your salary. Whether you rest or stay sick, this is the rule of company.[2.59]

Naksh, an Indian national working as an appliance group foreman at Bader H. Al-Hussaini & Sons Co (a sub-contracting company of Aramco) said that the company renews its worker’s Iqama every 3-4 years, leaving them vulnerable to the threats of being arrested, not being able to access free health care services, and not being able to travel to see their loved ones. He said, “The company is not renewing our residential I.D. It expired in December 2019. We asked the employer multiple times about renewing our iqama. They said “Insha’Allah, now we have no money. When we get money, we will definitely renew it. This company has the practice of renewing our iqama every 3-4 years only. Once, we all workers went to our sponsor and demanded that we want to get our iqama renewed. We did a written agreement with the company. The company manager and one Arab woman signed the agreement, but it was never executed. We are without Iqama now. We are not even eligible to return back to India. We need a valid iqama for the authorities to stamp on the exit visa. The worst part is that even our family is suffering because of this. We are not able to transfer money to our home. Whenever we want to transfer money to our family in India, we request our co-workers who have Iqama. They do not do it for free, they ask commission to transfer the money. It has been very difficult for us to send our salary to our home. In addition to that, we are not eligible for free health care services provided by the company without Iqama. We are not able to travel outside. We are fearful to even walk on the road because without Iqama, police can arrest us.[2.60]

Yagnesh, an Indian national working as a labourer at an Aramco site said his employer ignored his request to renew his Iqama. This has left him unable to access free health care facilities. He said, “I do not have access to free health services. As my Iqama has already expired, my health card also does not work. We have requested the company to renew or Iqama, but they ignore us. I face a lot of difficulties in getting treatment. I have to spend my own money to get health check-up. Upon that, they even deduct our salary if we have to take a sick leave.”[2.61]

An Indian national working at Aramco, Jubail, said the company is neither providing workers with medical facilities, nor are they renewing our Iqama. He told Equidem, “My Iqama has expired. The people of the company are not providing them medical facilities, nor are they renewing Iqama. Treatment is very expensive here. This is why many of us do not go to see a doctor even at the very last stage. Upon that, there is discrimination against migrant workers. They are not treated with respect or care at the hospitals. The company also reduces 100-300 riyal ($26-80) if anyone takes sick leave.”[2.62]

An Indian national working at Aramco said, “It has been 6 months since my Iqama expired. The company has not renewed it yet. It has created a lot of difficulty for me to get medical treatment. When I am not feeling well, I have to get medicine with my own money. The company also reduces same day’s salary if the workers take sick leave.”[2.63]

An Indian national working at Aramco said, “Many workers in the company do not have Iqama. My Iqama too expired 7 months ago. Due to this, me along with hundreds of other workers are not able to go to hospital. We buy simple medicine like pandol from the local pharmacy and call it a day. We do not get real treatment at the company. They are doing nothing to help workers in such situation. Even when we ask them to renew our Iqama, they ignore us.”[2.64]

An Indian national working at Aramco said, “My Iqama has expired in January, but the company is neither renewing my Iqama nor sending me back home. I am not entitled to free health care facilities without Iqama. I am scared that if I get infected, I will die without receiving treatment.”[2.65]

An Indian national working for Natrec, a sub-contractor of Aramco, said the company did not renew his Iqama even after he made multiple requests. He said:

My Iqama expired early January this year. I requested the people at the company to renew my Iqama, but they did not care. There are hundreds of workers who do not have Iqama at the company. This has put us in risk. None of us are able to go to hospitals because we do not have an Iqama.[2.66]

Workers employed by Azmeel Contracting Company on Aramco sites also complained about having expired residency permits and therefore being unable to access the public health system:

My Iqama expired last year. The company has not renewed it yet. Those workers who do not have Iqama, cannot get free treatment from the hospital. Many migrant workers do not have the money to get treatment at a private hospital. We mostly buy cheap medicines from the medical counter.[2.67]

Where they could afford it, workers who could not access the public health system had to pay for medical care. Viraj, who worked for International Recruitment Company on an Aramco site, spoke about his experience: The reason my health deteriorated in the first place was due to lack of protective equipment despite dangerous working conditions. Where I worked was very dangerous. I had to work in the middle of the gas plant, risking my life every day. They did not provide any security equipment to the workers. I felt that it was affecting my health. But whatever the cause of health problems, we had to spend our own money for treatment as the company refused to renew our Iqama. There were many workers in our company who could not access health care facilities because their Iqama had expired and the company had not renewed it.[2.68]