- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Research findings

- Conclusion

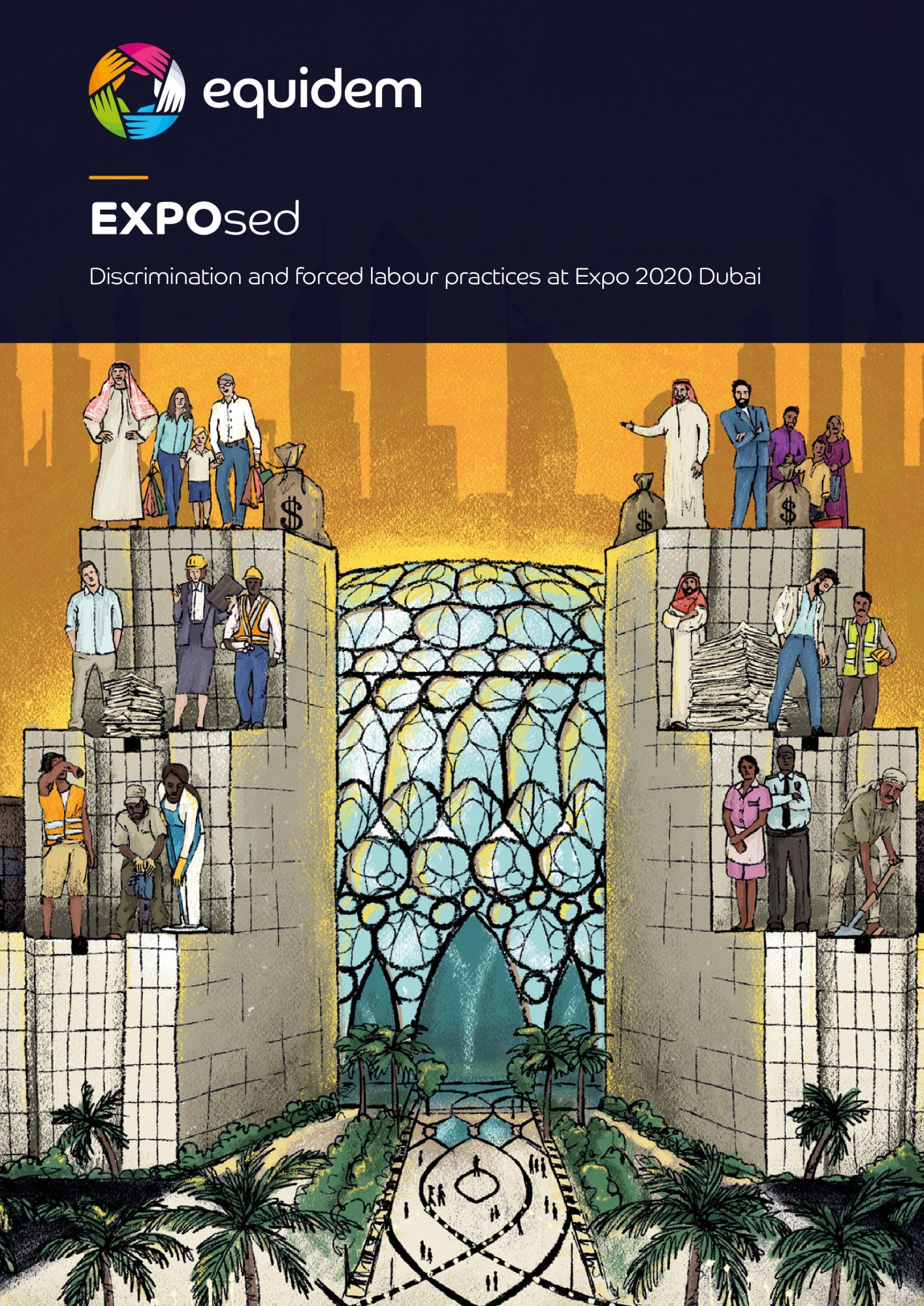

EXPOsed

Executive Summary

“We seek to build a better future for everyone while creating real impact that transforms our dreams into realities.” [0.1]

- EXPO 2020 DUBAI WEBSITE

“It’s very tiring. I work from early in the morning till evening ...

They promised me an increment in salary after probation - something I have not seen to date ... Never have I received overtime payments from my employer ... The way they treat the staff is like slaves, I mean modern day slavery.”[0.2]

- BABIK, [0.3] AN INDIAN NATIONAL WORKING FOR A CAFÉ AT EXPO 2020 DUBAI

The city of Dubai in the oil-rich Gulf kingdom of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) styles itself as an international hub for tourism, business, and culture. At the heart of this image is Expo 2020 Dubai, one of the largest megaprojects in the region and the first world expo held in the Middle East. Expo 2020 Dubai, delayed to 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, features 192 national pavilions. It is expected to attract 25 million visitors during the its six months of operation between October 1st, 2021 and March 31st, 2022, and potentially millions more after the Expo ends and the site is converted into District 2020 to attract business, high-tech innovation, and a residential population to the area.[0.4] Expo 2020 Dubai could not have taken place without migrant workers who make up more than 90% of private sector employees in the UAE.[0.5] These women and men were integral to building the infrastructure for the event, with more than 40,000 workers employed in the construction process alone.[0.6] Similarly, the delivery of the Expo requires thousands of additional migrant workers to perform a range of services, including in facilities management, security, hospitality and cleaning.

Equidem research between September and December 2021 reveals that migrant workers engaged on projects at Expo 2020 Dubai across a range of sectors – from hospitality and retail to construction and security – are being subjected to forced labour practices. These practices violate UAE law yet, as far as Equidem is aware, none have been investigated by the authorities, nor has any individual or business been brought to account. Workers also spoke of being subjected to racial discrimination and bullying, and a reluctance to make formal complaints about their treatment out of fear of reprisals from employers or the authorities. This is despite Expo organisers establishing labour complaint grievance mechanisms as part of wide-ranging worker welfare standards that are meant to apply to all individuals working at the event and which establish a higher threshold of protection than under the UAE’s labour laws.

Key findings

|

Main report findings |

|

|---|---|

|

Majority of Expo 2020 Dubai workers interviewed faced forced labour practices |

|

|

Workers subjected to racial discrimination and bullying |

|

|

Workers charged illegal recruitment fees |

|

|

Non-payment of wages and benefits |

|

|

Retention of passports |

|

|

Workers not accessing grievance mechanisms |

|

|

Forced labour at Expo 2020 Dubai |

|

|---|---|

|

The great majority of migrant workers interviewed for this research reported that they had experienced violations of their labour rights which are also indicative of forced labour: |

|

|

25 interviewees (83%) paid illegal recruitment fees and/or did not receive wages or other benefits on time and in full |

|

11 interviewees (37%) reported three or more issues at work which are indicators of forced labour |

|

5 interviewees (20%) reported five or more issues at work which are indicators of forced labour |

|

UAE law prohibits forced labour or any other practice that may amount to trafficking of persons under national law and international conventions. Yet the UAE rarely prosecutes forced labour and human trafficking cases, if ever. |

|

Security guards working for different private firms on Expo 2020 Dubai described treatment that is indicative of forced labour. © Equidem 2022

Women and men working in hospitality at Expo 2020 Dubai, said they were charged illegal recruitment fees, faced delays in receiving wages, and had passports confiscated, practices that are indicators of forced labour. Some also complained of being subjected to racial discrimination. © Equidem 2022

“My expectation was high when I came to Dubai, I thought these people will accept me for who I am, but as a migrant and being an African, I have gone through many bad experiences. I have been bullied based on my race. I have experienced that employees are not treated by the management equally. I am a first-class degree holder in my country and I have good work experience, (but) the guy who had less qualification and experience than me got a good position.” [0.7]

- FADHILI, A GHANAIAN SECURITY GUARD AT EXPO 2020 DUBAI

Racial discrimination and bullying

More than a third (37%) of workers stated that there was discrimination and/or bullying in the workplace and several gave examples of their direct experience of this. UAE law prohibits discrimination and hatred on the basis of caste, race, religion or ethnic origin.[0.8] Raz, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai, told Equidem, “Even when we are doing the same work, all those except the nationals are considered second category staff. We are getting less salary for the same work and the other work related benefits are also less. I experienced being bullied... by senior staff.” [0.9]

"Yes, they discriminate a lot when it comes to dividing work, the Asians are given heavy work and less pay while the Europeans and Arabs are given lighter roles with lots of income... The Asians were the first to lose their jobs which they work so hard for..."[0.10]

- IRFAN,A PAKISTANI CONSTRUCTION WORKER AT EXPO 2020 DUBAI

“There is a lot of discrimination amongst the nationalities at work. I witnessed a lot of discrimination, especially dark-skinned employees who didn’t have anyone to speak on their behalf when the company was looking to fire staff. Some of the workers were given redundancy but especially among the Africans, they were given redundancy without pay.” [0.11]

“There is a lot of discrimination amongst the nationalities at work. I witnessed a lot of discrimination, especially dark-skinned employees who didn’t have anyone to speak on their behalf when the company was looking to fire staff. Some of the workers were given redundancy but especially among the Africans, they were given redundancy without pay.” [0.11]

- GHECHE, WORKING IN HOSPITALITY AT EXPO 2020 DUBAI

Workers charged illegal recruitment fees

More than half (57%) of those interviewed had paid recruitment costs despite this being prohibited under UAE legislation and the Expo’s own standards. The average amount paid was US$1,006, with charges ranging from US$2,069 to US$50. Several participants stated that their employers were aware that the agencies they used were charging migrants recruitment fees. The UAE law requires the recruitment cost to be borne by the employer. [0.12] Sabir, who works for a private security firm, at Expo 2020 Dubai said, “I paid an amount of 100,000 Indian Rupees (US$1,322) for the recruitment agency. ... The company knows about the processing charge because it routinely hires recruitment agencies to facilitate their work when they need a lot of employees.”[0.13]

Non-payment of wages and benefits

Two thirds of workers said that their wages or other benefits were not always paid on time or in full. The most common complaints involved the non-payment of wages, overtime and annual increments; salary reductions; and late payments. The latter issue caused particular hardship when the employee’s food allowance was included as part of their salary. UAE law requires employers to subscribe to the Wage Protection System (WPS) and pay as per the due date.[0.14] Expo 2020 Dubai Worker Welfare Policy also requires employers to pay employees’ wages and benefits on time and in full. Gheche, working in hospitality at Expo 2020 Dubai told Equidem, “I feel like they should improve the living and working conditions. ... They promised they would review the salary every year which they didn’t do... They never paid my overtime.”[0.15]

"I never received any overtime and am always working for more than nine hours every day.”[0.16]

- IRFAN,A PAKISTANI CONSTRUCTION WORKER AT EXPO 2020 DUBAI

|

About the workers interviewed |

|

|---|---|

|

69 one-on-one interviews with migrant workers in Dubai working at Expo 2020 Dubai (30 semi-structured interviews and 39 unstructured interviews) between September and December 2021. All worker names changed to protect their identity. |

|

|

11 different nationalities |

|

|

77% of workers interviewed were from Bangladesh, India, Kenya, Nepal and Pakistan. The rest were from 6 different African countries |

|

|

22 of the interviewees were men (73%) and 8 were women (27%) |

|

|

33 the average age of the women and men interviewed, whose ages ranged from 24 to 42 |

|

Retention of passports

Only one of the workers interviewed by Equidem was in possession of their passport, and both he and other interviewees stated that it was common practice for companies to retain their employees’ travel documents. UAE law prohibits employers from confiscating the passport of their employees and has declared the same as illegal.[0.17] Just over two thirds of interviewees said they could retrieve their passports when they needed to travel abroad or for official purposes (e.g. to renew their contract).

But they did not appear to have free access to their documents and had to explain why they needed them. One company forced its workers to sign forms saying that their passports had been returned to them when this was not the case. Chandra, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai told Equidem, “My employer has my passport. The company made us sign a paper saying we have received our passport. In reality, it is still in the office of our accommodation camp ”.[0.18]

“My employer has my passport. After we started working at the site, the site’s worker welfare person gave instructions to the company saying they had to return workers’ passports. The company made us sign a paper saying we have received our passport. In reality, it is still in the office ofour accommodation camp.”[0.19]

- CHANDRA, A NEPALI SECURITY GUARD AT EXPO DUBAI

Workers not accessing grievance mechanisms

None of workers reported or tried to address any of the problems they had at work. Several were unwilling to file complaints because they feared they would be subject to reprisals and/or it would not achieve anything. Fadhili, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, “I have never raised any complaint on the bullying, because I know there will not be any change if I make any complaint. I want to continue my job as I have some financial problems.”[0.20] Others were unaware of their rights or did not know how to resolve work-related grievances. None of the interviewees received information on their rights as required under the Expo’s own worker protection standards, either at Dubai airport or from their employer[0.21] and a third of participants stated that they were not given a copy of their contract in their native language.[0.22] Furthermore, only 10% of workers interviewed were told about key mechanisms for reporting work-related problems, namely the Worker Welfare Committees, the Worker Connect app or the Expo 2020 Dubai hotline.

All 69 individuals interviewed for this report spoke of their intense fear of reprisals from employers or the Emirati authorities, such as the police, for talking about their situation. Equidem took significant precautions to prevent and mitigate any adverse impact on researchers and the individuals who spoke to them. Equidem wrote to the UAE authorities, Expo 2020 Dubai organisers and individual businesses about the cases documented in this report. Equidem spoke to a representative of Expo 2020 Dubai responsible for worker welfare who said she could not comment as it was a matter for the event’s Higher Committee. As at timing of publication, neither Expo 2020 Dubai’s Higher Committee nor the UAE authorities had responded, despite being notified in writing before publication of this report. Only two out of thirteen companies contacted regarding complaints about working conditions made any response to Equidem.

Conclusion

Expo 2020 Dubai companies not complying with Worker Welfare Standards

None of the companies employing the 30 migrant workers interviewed at length for this research were fully complying with their contractual obligations as set out in the Worker Welfare Policy and accompanying Assurance Standards or the UAE’s labour laws. This ranged from not properly performing their due diligence (e.g. checking whether recruitment fees had been paid or providing employees with written information on their rights at work) for being involved or complicit in breaking laws (e.g. not paying wages in full and on time, retaining passports or allowing recruitment fees to be charged).

"I paid a commission of about US$50 to be able to go through the interview - I didn’t see the reason why they were asking for it... I came to learn that it was illegal after paying the recruitment fees and I inquired, but then the person who gave us the job told us it was a way of thanking him for letting me through the job, I wasn’t satisfied fully, but I had to accept it and move on with life.”[0.23]

- HIARI, A ZIMBABWEAN SECURITY GUARD AT EXPO 2020 DUBAI

|

UAE failing to protect migrant workers from forced labour |

|

|---|---|

|

Expo 2020 Dubai companies not complying with Worker Welfare Standards |

|

|

UAE authorities not enforcing labour protections |

|

|

Prohibition on trade unionism limits worker access to remedies |

|

|

New UAE labour law doesn’t address non-compliance and lack of enforcement |

|

“I have been working in UAE for 15 years and none of my employers has given any information about my rights as an employee.”[0.24]

- JWALA, AN INDIAN SECURITY GUARD AT EXPO 2020 DUBAI TOLD

“They didn’t provide the contract to me. I signed the contract paper and gave it back to the employer. The offer letter was described in English. All the official papers are explained in English and Arabic and we didn’t get any written documents in our native language.”[0.25]

- RAZ, A PAKISTANI SECURITY GUARD AT EXPO 2020 DUBAI

UAE authorities not enforcing labour protections

The UAE authorities are also failing to properly monitor and enforce the law. This research found numerous examples of labour rights violations involving unpaid overtime, salary deductions, bullying and discrimination, passport confiscation and recruitment charges.

However, in 2020, the labour inspectorate only identified two cases across the whole of the UAE in which any of the above abuses took place.[0.26] Similarly, more than a third (37%) of participants in this research reported three or more issues at work which are indicators of forced labour, yet the UAE has never convicted any one for a forced labour offence.[0.27]

Prohibition on trade unionism limits worker access to remedies

The procedures for resolving issues at work and remedying labour rights violations are not working effectively, as reflected in the fact that none of the 30 interviewees used them to try and address the problems they were having at work. One of the key reasons for this is that an employee’s ability to assert their rights is severely compromised by the fact that the UAE does not permit workers to freely associate or join an independent union.[0.28] This makes it extremely difficult for an employee to access advice and support in a dispute at work or to successfully challenge a decision taken by their employer.

New UAE labour law does not address non-compliance and lack of enforcement

On 2 February 2022, Federal Law No.33 of 2021 comes into effect and updates the labour regulations governing the private sector.[0.29] While this new law does contain some significant reforms which should be wel comed (e.g. the introduction of a minimum wage; a prohibition on all forms of discrimination; and the introduction of new visa categories), it is too early to assess what practical impact it will have as many of the details will be determined in regulations (e.g. what the minimum wage will be and how workers will change their sponsors under the new visa regime).[0.30]

However, it is clear that Federal Law No.33 does little to address non-compliance with existing legislation by employers or the inadequate investigation and enforcement of the regulations by the UAE authorities. Both these issues are serious problems, as is evidenced in this report. Furthermore, the new law does not correct the imbalance of power between migrant workers and their employers which makes it difficult for those experiencing labour rights abuses to seek or obtain effective remedies. Federal Law No.33 does not amend the current legislation to permit migrant workers to freely associate, organise, bargain collectively or form trade unions, nor does it guarantee workers access to independent and professional advice and representation to assist them in taking forward a complaint.

UAE must address disconnect between formal protections and reality of forced labour practices

On paper, the UAE and Expo 2020 Dubai have established robust requirements for the protection of migrant worker’s labour rights. Despite this, Equidem has uncovered non-compliance across a range of labour law and welfare standards and in multiple different sectors. This indicates a significant disconnect between the Emirate’s stated ambition of being a modern, international state and the reality of racial discrimination and forced labour practices that migrant workers are facing. With 192 country pavilions and some of the largest consumer brands as sponsors and partners, practically every major economy in the world is represented at the Expo. The UAE’s failure to protect migrant workers from forced labour also exposes its foreign state allies and international business partners at serious risk of liability for human rights violations in the country. If women and men are being subjected to these exploitative practices at Expo 2020 Dubai, where the resources available for monitoring labour compliance and the standards applied are higher than the national labour regime, questions must be raised about the risks of forced labour and other forms of exploitation in the UAE more broadly. Without active enforcement and recognition of workers’ rights to freedom of association, collective bargaining, and other trade union rights, the UAE’s new labour laws will do little to address the country’s labour exploitation crisis.

192 countries representing every major economy and country have pavilions at Expo 2020 Dubai. These include every country of origin of workers that have been subjected to forced labour practices at Expo. © Equidem 2022

Summary of recommendations (see 3.1 for full list)

Equidem is calling on the United Arab Emirates authorities to:

- Investigate and enforce all labour laws, effectively implement the law prohibiting discrimination, and effectively execute equal pay for equal work.

- Bring to justice individuals and organisations responsible for the exploitation of migrant workers at Expo 2020 Dubai in line with international human rights standards.

- Revoke Resolution No.279 (2020), allowing companies to reduce migrant workers’ wages temporarily or permanently.

- Pass legislation recognising workers’ right to freely associate, organise, bargain and form a trade union in line with international labour conventions.

- Respect migrant workers’ right to freely change jobs without prior permission or penalties

- Publicly release labour complaint information through an independent and impartial mechanism.

- Permit independent observers access to the UAE to monitor the treatment of migrant workers and issue an open invitation to all United Nations Special Procedures so that independent UN experts can review the UAE’s compliance with its international human rights obligations.

- Provide long-term migrant workers with the opportunity to apply for permanent residency and citizenship.

Equidem is also calling on states and businesses represented at Expo 2020 Dubai to: conduct independent labour assessments on their sites at the megaproject. Where credible information of forced labour and other human rights violations are identified, these should be formally brought to the UAE authorities with a view to bringing perpetrators to justice and providing remedies to all victims.

Introduction 1

1.1 Background

"It’s a bit stressful. Waking up very early, I mean 3.00am, take the 4.00am bus, then arriving to work at around 5.10am. Then work the whole day, standing 12 hours from 6.00am to 6.00pm. ... The nature of the job is demanding and challenging and sometimes I feel like I am tired and fed up, but I remember my daughter and mum. Then I am motivated to work.” [1.1]

- CHUKI, A ZIMBABWEAN SECURITY GUARD AT EXPO 2020 DUBAI

World Expos are international trade fairs, and they give countries from all over the world the chance to promote their business, culture and new technology. Expo 2020 Dubai, delayed to 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, is the first Expo to be held in the Middle East and provides the United Arab Emirates (UAE) with a unique opportunity to showcase its ability to host a global megaproject.

The event features 192 national pavilions and is expected to attract 25 million visitors during the six months it operates (1 October 2021 to 31 March 2022). After Expo 2020 Dubai closes, the site will be converted into District 2020, with 80% of Expo buildings being repurposed to attract business, high-tech innovation and a residential population to the area.[1.2]

Expo 2020 Dubai in numbers

192 – countries with pavilions at Expo 2020 Dubai including the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Germany, Australia, Japan, China, India, South Korea and Kenya

$7 billion trade fair – estimated value of the Expo 2020 Dubai

Construction of Expo 2020 Dubai: 50 main contractors, over 2,000 subcontractors, more than 40,000 workers,[1.3] along with thousands of additional workers to perform a range of services, including facilities management, security, hospitality and cleaning

> 90% of workers employed in the United Arab Emirates private sector are migrants[1.4]

The infrastructure and logistical challenges of hosting this prestigious $7 billion trade fair are significant. For example, the construction element of the Expo alone included 50 main contractors, over 2,000 subcontractors and more than 40,000 workers.[1.5] The delivery of the Expo 2020 Dubai also requires thousands of additional workers to perform a range of services, including facilities management, security, hospitality and cleaning. Consequently, the Expo has led to a substantial increase in the demand for migrant workers in the UAE, even though foreign nationals already account for more than 90% of workers employed in the private sector.[1.6]

In recent years, there have been regular reports of migrant workers being subjected to serious labour rights violation in the UAE, including: contract substitution, excessive working hours, non-payment of wages, the confiscation of identity documents and forced labour. Based on these concerns, in September 2021, the European Parliament urged nations not to take part in Expo 2020 Dubai, citing the UAE’s “inhumane practices against foreign workers” which it said had worsened during the pandemic. [1.7]

In November 2021, Sharan Burrow, the General Secretary of the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), warned that:

"... the Expo 2020 Dubai has increased the risks of modern slavery for governments, international organisations, and businesses with pavilions and associated events at the Expo."[1.8]

However, the UAE Government has described this global world fair as a unique opportunity to raise employment standards.[1.9] The body responsible for organising the Expo 2020 Dubai has stated that

Expo 2020 Dubai would not be possible without the thousands of workers who built, maintain and provide services to the event. © Equidem 2022

it is committed to ensuring the highest standards for its workforce and described Expo 2020 Dubai as a unique opportunity to secure “a positive impact and a meaningful legacy for worker welfare.”[1.10] It has also underlined that all organisations supporting the delivery of the Expo, including third party developers, contractors and partners, must:

... demonstrate effective leadership on worker welfare and allocate sufficient resources to ensure that employment conditions throughout their supply chain meet our requirements.[1.11]

These requirements are set out in its Worker Welfare Policy and accompanying Assurance Standards and incorporated into every Expo 2020 Dubai contract. The purpose of this report is to investigate whether there has been full compliance with these labour standards in relation to migrant workers, during both the construction and delivery of the megaproject.

Expo 2020 Dubai labour protections

All companies involved in the Expo 2020 Dubai must comply with its Worker Welfare Policy and accompanying Assurance Standards. These require employers to adhere to the following provisions:

Ensure fair and free recruitment

Ensure that employees understand the terms and conditions of their employment

Treat employees equally and without discrimination

Protect and preserve the dignity of employees and not tolerate harassment or abuse of any kind

Respect the right of employees to retain their personal documents

Pay employees’ wages and benefits on time and in full

Allow employees freedom to exercise their legal rights without fear of reprisal

Provide a safe and healthy working environment

Provide access to grievance mechanisms and remediation

Ensure that bonded, indentured, forced, or child labour is not used[1.12]

1.2 Methodology

This report is based primarily on 30 semi-structured, one-to-one interviews carried out confidentially with migrant workers in Dubai between September 3rd and December 2nd 2021. A further 39 other unstructured interviews were conducted with migrants working on Expo 2020 Dubai for background information. Interviewees had to be migrant workers who were involved in delivering services for the Expo and who reported having had a work-related problem.

Efforts were also made to ensure that the profile of interviewees reasonably reflected the gender and nationality representation of the Expo workforce. Interviewees were nationals of 11 different countries, with migrant workers from Kenya, Nepal, Pakistan, India and Bangladesh making up more than three quarters of the total (77%), and the rest coming from six different African countries. Twenty-two of the interviewees were men (73%) and eight were women (27%).

Research participants worked in a variety of sectors, including hospitality, construction, cleaning, security, customer care, logistics and facilities management. All the migrant workers who took part in the research were between the ages of 24 and 42, with the average age being 33. Interviewees were asked questions to gauge the extent to which the Expo 2020 Dubai Worker Welfare Policy[1.13] was being adhered to by employers, including around key issues such as: recruitment fees; payment of wages; discrimination or abuse; retention of identity documents; and access to redress mechanisms.

Interviews were conducted just prior to and after the official start of Expo 2020 Dubai so that participants could relate their experiences of working on both the preparation and the delivery of event. There were significant challenges in identifying migrant workers who were willing and able to take part in the research as potential interviewees were afraid of the authorities and that they would be subject to reprisals, including losing their jobs, if they spoke about their experiences.[1.14] In addition, it was also difficult to access potential interviewees due to their long working hours, limited time off and the fact that many had long distances to travel to and from work. As Irfan, a construction worker at Expo 2020 Dubai noted: “I don’t have time to socialise, only to work and go home to rest.”[1.15] To protect the migrant workers who participated in this research, their real names have not been used and any identifying information has been removed from the report. Equidem took significant precautions to prevent and mitigate any adverse impacts on researchers and the individuals who spoke to them.

A literature review was carried out to identify measures taken by the UAE Government to protect migrant workers’ rights and any reports of non-compliance with the provisions of the Worker Welfare Policy and the UAE’s labour laws.

Equidem wrote to the UAE authorities, Expo 2020 Dubai organisers and the individual businesses engaging workers featured in this report about the various cases of unfair labour practices and related issues. As at timing of publication, neither Expo 2020 Dubai’s Higher Committee nor the UAE authorities had responded, despite being notified in writing before publication of this report. Only two out of thirteen companies contacted regarding complaints about working conditions made any response to Equidem.

Research findings 2

The research findings set out below have been grouped into sections which reflect the key labour standards that employers must comply with under the Expo 2020 Dubai Worker Welfare Policy.

2.1 Ensure fair and free recruitment

UAE legislation prohibits recruitment agencies from soliciting or accepting any fees from workers. This is set out in the Labour Law, Ministerial Decree No. 52 of 1989, Ministerial Decree No. 1283 of 2010 and Cabinet Decision No. 40 of 2014, as well as in the Standard Employment Contract of 2015 and the Worker Welfare Policy.[2.1] The Worker Welfare Assurance Standards, which apply to all workers engaged by companies involved in the delivery of the Expo 2020 Dubai, specifically state that “where recruitment fees have been paid by the worker to a UAE or overseas registered recruitment agency, these will be reimbursed by the employer” and that “employers must undertake assessments to check whether workers have paid fees during the recruitment stage.”[2.2]

The Expo 2020 Dubai Committee has also underlined that:

Our Policy and Assurance Standards both clearly state employers must ensure the free and fair recruitment of workers. That means all recruitment costs – including visas, airline tickets, and any other administrative costs – must be covered by employers without exception, and absolutely no fees should be paid by workers. If, during our monitoring, we discover fees have been paid, workers have been reimbursed.[2.3]

The ILO has repeatedly urged the UAE Government to ensure that the legislation cited above is effectively applied and that migrant workers are protected from abusive practices linked to the imposition of recruitment fees. It also recently asked the UAE Government provide information, including statistical data, on action it has taken in this regard.[2.4]

Despite all of the above, more than half (57%) of those interviewed for the research had paid some recruitment fees or costs. The average amount paid by these migrant workers was US$1,006 dollars with charges ranging from US$2,069 to US$50. These are substantial sums for low-wage migrant workers. Rudra, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "I had to pay 200,000 Nepalese Rupees (US$1,652) to the recruitment agency.[2.5] Only after I came here, I came to know that it was a free visa, free ticket job. I had no choice but to give the money to secure my employment."[2.6]

Fadhili, a Ghanaian Security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, “Before the recruitment, the agency authorities explained to me about the recruitment cost. My monthly salary was 3,000 AEDs[2.7] (US$817), so I had to pay one month salary to them.”[2.8] Hiari, a Zimbabwean security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, “I paid a commission of about US$50 to be able to go through the interview - I didn’t see the reason why they were asking for it... I came to learn that it was illegal after paying the recruitment fees and I inquired, but then the person who gave us the job told us it was a way of thanking him for letting me through the job, I wasn’t satisfied fully, but I had to accept it and move on with life.”[2.9]

None of interviewees were asked by their employer if they had paid any recruitment costs, although this is required under the Worker Welfare Policy. Worse still, several participants stated that their employers were aware that the agencies they used were charging migrants as part of the recruitment process. Sabir, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, “I paid an amount of 100,000 Indian Rupees (US$1,322) for the recruitment agency. They arranged everything for me until I reached Dubai. ... The company knows about the processing charge because the company routinely hires recruitment agencies to facilitate their work when the company needs a lot of employees.”[2.10]

Raz, a Pakistani security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai told researchers, “I paid 3,500 AEDs (US$953) for my recruitment agency ... The management is giving permission to many recruitment agencies and all of them had their own processing charge. The companies didn’t interfere on that.”[2.11] Tahoor, who works for Arkan Security Management at Expo 2020 Dubai said, “I attended the interview through a consultancy and I have paid an amount of 3,000 AEDs (US$817) for them... the company is giving permission for the consultancies and the payment is processing fees.”[2.12] Indra, a cleaner at Expo 2020 Dubai said, “The agency took 75,000 Nepalese Rupees (US$619) as recruitment fee... My employer did not ask about the recruitment fee. I am not aware of having signed anything relating to the recruitment fee as well. I just did everything the agency told me to do.”[2.13]

Of those workers that paid recruitment costs, none appeared to be aware that they could ask for this money to be reimbursed, although this should have been explained to them as part of their induction.[2.14]

Many migrant workers have to borrow money to pay recruitment fees and this often leaves them in debt and vulnerable to exploitation or forced labour. For example, one woman from Kenya who was interviewed for this research took a loan to pay her agency’s fees of US$700. The interest rate on this loan was US$300.[2.15]

It should also be noted that seven of the interviewees who did not pay recruitment fees were hired in the UAE after travelling there on a visitors’ visa and would therefore already have paid some of the costs associated with taking up a job abroad themselves.

Expo 2020 Dubai is expected to attract 25 million visitors during its six months of operation between October 1st, 2021 and March 31st, 2022, and potentially millions more after Expo ends and the site is converted into District 2020 to attract business, high-tech innovation, and a residential population to the area. © Equidem 2022

“I migrated as a tourist (on a three-month visitor’s visa), which included paying my own tickets, and coming with a dream to get a job in UAE.”[2.16]

AKIN, A MAN FROM NIGERIA WORKING IN A FACTORY. INTERVIEWED ON 12 SEPTEMBER 2021

2.2 Ensure that employees understand the terms and conditions of their employment

The UAE Ministry of Human Resources and Emiratization (MOHRE) requires prospective workers to sign a Standard Employment Contract which is filed with the Ministry before a work permit is issued.[2.17] None of the clauses in the Standard Employment Contract can be amended without the explicit authorisation of the Ministry and it must be issued in three languages (Arabic, English and the mother tongue of the worker).[2.18] Expo 2020 Dubai’s Worker Welfare Assurance Standards also specifically state that:

A translated version of employment offer will be provided to the worker, at the time of recruitment, in the worker’s native language.[2.19]

These measures are designed to prevent contract substitution and ensure that workers understand their rights and obligations under their contract.

However, one third of the interviewees stated that they were not given a copy of their contract in their native language. In general, these respondents received a letter in English with the job offer. Raz, a Pakistani security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai told researchers "They didn’t provide the contract to me. I signed the contract paper and gave it back to the employer. The offer letter was described in English. All the official papers are explained in English and Arabic and we didn’t get any written documents in our native language."[2.20] Tahoor, who works for Arkan Security Management at Expo 2020 Dubai told Equidem, "The company didn’t provide the employment contract. I have got the job offer letter which was explained in English. I just saw the last page of my employment contract when I was signing it."[2.21]

Hamza, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "I got a job offer letter when I successfully passed the interview. It was written in English. They do not give the contract to employees, we should sign and give it back to them."[2.22] Muluk, an Indian security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai told Equidem, "When I got selected, they provided me the job offer letter which described the nature of my job and other details including salary, leave and other benefits. All the details were in English. ... I didn’t get the official information in my native language."[2.23]

It should also be noted that of those who did receive their contract, 15 stated that it was in English and, while they said they could read and understand the contract, English was generally not their native language.

It is crucial that employees receive a copy of their official contract which details all the terms and conditions of their job in their native language, so that they fully understand their rights and responsibilities and are better able to challenge any exploitative practices. This is particularly important given that employees’ terms and conditions of work may vary considerably. Gheche, working in hospitality at Expo 2020 Dubai told Equidem, “... everyone gets his or her own salary separately and according to the agreement they had with the employer, which is different with everyone.”[2.24]

2.3 Pay employees’ wages and benefits on time and in full

In 2009, the UAE established the Wage Protection System (WPS) to help ensure that workers receive their wages on time and in full. The WPS is an electronic salary transfer system and private companies employing more than 100 employees are required to use it to pay their workers via approved banks and other financial institutions. Employers that fail to use the WPS can be fined under Cabinet Decision No. 40 of 2014. Companies who do not pay their workers’ wages on time can also be fined or subject to other administrative sanctions, as set out in Ministerial Decree No. 739 of 2016.[2.25]

The MOHRE monitors payments made through the WPS electronically and if payments are not made after 16 days it can freeze new work permits for that employer. If non-payment continues past 29 days, the Ministry can refer the case to the labour courts and, after 60 days, a fine of 5,000 AED ($1,362) per unpaid worker is imposed, up to a maximum of 50,000 AED ($13,623).[2.26]

The ILO Committee of Experts has called on the UAE Government to ensure that Ministerial Decree No. 739 of 2016 (adopted to ensure the payment of wages without delay) and the WPS are:

... implemented effectively, so that all wages which are due are paid on time and in full, and that employers face appropriate sanctions for the non-payment of wages. The Committee also requests the Government to provide information on the penalties effectively applied for non-payment of wages.[2.27]

Despite the measures taken by the Government and the concerns raised by the ILO, non-payment and late payment of wages continues to be a key issue affecting migrant workers. In 2020, the UAE’s National Committee to Combat Human Trafficking (NCCHT) reported that the Government had issued 8,181 fines to companies that failed to provide payments to workers via the WPS in 2020.[2.28] This indicates that thousands of companies are still not complying with this legal obligation more than 10 years after the WPS was introduced.

Furthermore, the U.S. Department of State noted in 2021 that some companies were circumventing the WPS and not paying migrant workers their full salaries:

Media and diplomatic sources continued to report that some companies retained workers’ bank cards or accompanied workers to withdraw cash, coercively short changing the employees even though the WPS showed the proper amount paid.

Such cases were difficult to prove in labor courts, given the WPS documented accurate payments via designated bank accounts.[2.29]

Non-payment of wages is also an issue for workers involved in Expo 2020 Dubai. Two thirds of the migrant workers interviewed for this research stated that their wages or other benefits were not always paid on time or in full. Several respondents complained that they received their salaries up to 10 days late and that this caused significant hardship for them and their families, particularly when their food allowance was part of their salary. Chuki, a security guard: Expo 2020 Dubai told Equidem, "Salaries are sometimes delayed by up to 10 days and this really inconveniences me because my dependants are waiting back at home and it’s difficult to fulfil my responsibilities... They give it (the food allowance) to us with the salary ... but when it’s late again I have to borrow from my colleagues in the upper grade."[2.30] Irfan, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "The salary they pay, but always delaying with up to 10 days... There has been always delays as they tell us the person in charge of signing our cheque for payment is always out of the country at the time, we are supposed to receive our salaries, which has never changed with or without COVID."[2.31]

Respondents also frequently complained that they did not receive overtime payments or the annual increments that they had been promised. Overtime pay is a crucial issue for migrant workers as many work significantly longer than the standard eight-hour day. Babik, who works for a Café at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "It’s very tiring. I work from early in the morning till evening (8.00pm) ... They promised me an increment in salary after probation - something I have not seen to date ... Never have I received overtime payments from my employer ... The way they treat the staff is like slaves, I mean modern day slavery."[2.32] Gheche, working in hospitality at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "I feel like they should improve the living and working conditions. ... They promised they would review the salary every year which they didn’t do. ... I have never been paid for the overtime I have done."[2.33]

Irfan, a construction worker at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "I never received any overtime and am always working for more than nine hours every day."[2.34]

Chuki, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "I feel they can do more in terms of focusing on the people working for them rather than only focusing on the work to be done. ... The contract said we will get overtime but I never got any overtime payment."[2.35] Hiari, a woman security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "... they promised a review every year, but I didn’t see any review being reflected on my salary. ... I never received overtime even though I worked for extra hours for most events."[2.36]

Participants also reported that non-payment of wages and reduced salaries was a widespread problem following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. On 26 March 2020, the MOHRE passed Resolution No.279 which allows private sector companies affected by regulations to limit the spread of COVID-19 to alter the terms and conditions of migrant workers’ contracts.

These measures apply exclusively to non-UAE employees and allow companies to grant employees unpaid leave and reduce their wages temporarily or on a permanent basis. While a worker must consent before an employer can change their salary, in reality migrants had little option as the alternative was that they would be made redundant. This was particularly evident during the initial period of the lockdown, which began in March 2020.

In previous research conducted in 2020, Equidem documented nine cases involving migrant workers who were employed by four separate contractors working on Expo 2020 Dubai who were not paid wages owed to them. The following testimony was typical of their experiences:

After the lockdown started, the company completely neglected its workers. I did not get my five months’ salary. They used to shout at me just for asking for my salary. They said, ‘no one will get salary for this lockdown period.’ After that, I was fired from work without any notice. The only explanation we got was that the company was making a loss. The company said they will transfer my salary amount once I got home. I have not got anything yet.[2.37]

Equidem submitted the finding from its 2020 research to the Expo 2020 Dubai Committee, but these practices persist, in violation with Expo 2020 Dubai’s required standards and the UAE’s labour laws. Interviewees in the current research repeatedly mentioned how their wages were reduced following the lockdown and/or their working hours and responsibilities were increased without additional pay, as they had to cover the work of colleagues who had been laid off.

Irfan, a construction worker at Expo 2020 Dubai told Equidem, "... they had laid off those long serving staff in the company, forcing us to work more hours than the stipulated hours in the contract without extra pay... we worked for more than 12 hours because they had let go the staff."[2.38]

Babik, who works for a Café at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "Jobs changed because we worked longer than usual as they had laid off manpower ... they ended up overworking us during the pandemic without extra pay ... They reduced our salaries for a long time by 50% to 75%."[2.39] Koel, who works for hospitality at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "... after they recalled me I was being paid only 50% for about six months, until after a year that’s when I got my full salary."[2.40]

Sharmin, who works in the administration of a company at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "I work 10-14 hours more often than not, due to operational requirements... Working hours have increased, with multiple responsibilities."[2.41]

Information provided by the research participants indicates that salary reductions ranged from 5% to 75% and generally lasted between three months and a year. However, several interviewees also noted that their terms and conditions of work have recently been amended or appear to have been permanently changed. Firyali, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai told Equidem, "... we were on 50% salary reduction and to add to that there was lots of delays on salaries... (now) we have new contracts with less benefits, this might change if the company regained the losses they incurred during the COVID-19 pandemic."[2.42]

Information provided by the research participants indicates that salary reductions ranged from 5% to 75% and generally lasted between three months and a year. However, several interviewees also noted that their terms and conditions of work have recently been amended or appear to have been permanently changed. Firyali, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai told Equidem, "... we were on 50% salary reduction and to add to that there was lots of delays on salaries... (now) we have new contracts with less benefits, this might change if the company regained the losses they incurred during the COVID-19 pandemic."[2.42]

Chuki, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "The contracts are now short term and the benefits have been decreased drastically, making (it)... easier to manipulate employees."[2.43] Chandra, a Nepali security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai told Equidem, "As we work in the Site, we get extra bonus as well. In the beginning, we used to get extra 500 AED (US$136). Recently, company started giving only 75 AED (US$20)"[2.44] Sabir, an Indian security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "We were also getting overtime payment which they also deducted very recently."[2.45]

2.4 Respect the right of employees to retain their personal documents

The confiscation or retention of workers’ documents is prohibited in the UAE by the Ministry of Interior’s Circular No. 267 of 2002, the Standards Employment Contract and the Worker Welfare Policy. However, the Government does not adequately enforce these laws and this practice remains pervasive, as noted by both the International Labour Organization (ILO)[2.46] and the U.S. Department of State:

In violation of the law, employers routinely held employees’ passports, thus restricting their freedom of movement and ability to leave the country or change jobs. ... There were media reports that employees were coerced to surrender their passports for “safekeeping” and sign documentation that the surrender was voluntary.[2.47]

Only one of the migrant workers interviewed for this research had their passport in their possession and both he and other interviewees stated that it was common practice for companies to retain their employees’ passports. Rudra, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said,

Before starting job at the Venue, my employer kept my passport, but now, since I started working at Venue, they gave it back. Other workers from the company, who do not work at the Venue, do not have their passport with them. The company has it. If they need to travel, the company gives it back, and when they return, the company takes it again.[2.48]

Mankaji, a house keeping supervisor at Expo 2020 Dubai told Equidem, "My employer has my passport. I have Emirates ID card, which is provided after we get visa for UAE. ... Usually, it is a trend in the UAE that employers keep their workers’ passport for safety. Whenever I need to travel, the company gives it back, and I deposit it with the company as I return."[2.49]

While just over two-thirds of interviewees stated that they could retrieve their passports when they needed them to travel abroad or for official purposes (e.g. to renew their contract), they did not appear to have free access to their documents and had to explain why they needed them. One interviewee said they had to make a formal request in writing to get their passports. Fadhili, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "All the employees’ passports are with the employer and they provide it on the time of our vacation. If we need it for any official purposes, like Embassy related purposes, we should submit a request letter and even then, they will give it to us only when they realize it is absolutely necessary."[2.50]

None of the interviewees indicated that they could unconditionally access their passports at any time; were given a choice regarding whether the company held their passports or not; or that their employer had offered personal and secure facilities to workers who wished to retain their documents. All the above are clearly set out as obligations for employers in the Worker Welfare Assurance Standards.[2.51]

One interviewee described how his company forced its workers to sign forms saying that their passports had been returned to them when this was not the case. Chandra, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai told Equidem, "My employer has my passport. After we started working at the site, the site’s worker welfare person gave instructions to the company saying they had to return workers’ passports. The company made us sign a paper saying we have received our passport. In reality, it is still in the office of our accommodation camp."[2.52]

Where migrant workers do not have immediate and unconditional access to their passports it increases the likelihood of their being forced to stay in a job against their will, creating a significant vulnerability to forced labour and other exploitation.

2.5 Provide a safe and healthy working and living environment

In October 2021, Expo 2020 Dubai acknowledged that there had been three work-related fatalities and 72 serious injuries during the construction of the Expo,[2.53] and that a further three workers had died from COVID-19. [2.54] However, there are concerns that these figures do not fully reflect the total number of injuries or coronavirus deaths. The Associated Press noted that the authorities had not provided overall statistics on these issues despite repeated requests[2.55] and the U.S. State Department also observed in 2021 that the “authorities typically did not disclose details of workplace injuries and deaths, including the adequacy of safety measures.”[2.56]

During the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was clear that many migrant workers in the UAE were living in unhealthy and unsafe accommodation. This was documented in research carried out by Equidem in 2020[2.57] and reported by the U.S. Department of State in 2021:

... some low-wage foreign workers faced substandard living conditions, including overcrowded apartments or unsafe and unhygienic lodging in labor camps.[2.58]

Nine interviewees in the current research (30%) did not consider the standard of the accommodation and food provided by their employers to be adequate and/or raised other concerns about their working or living conditions being unsafe or unhealthy. The issue that came up most often, including amongst those who did describe the accommodation as adequate, was the lack of space and privacy that resulted from having to share a small room with several colleagues. Irfan, a construction worker at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "I’m sharing a room with five colleagues making it uncomfortable and my privacy is compromised."[2.59]

Atir, a cleaner at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "They provide shared accommodation which doesn’t go so well because we are sharing six people in a room."[2.60] Chuki, working as a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai told researchers, "I am in a shared room with five more colleagues from other nationalities making it so difficult to cope as each individual comes with their character and attitude."[2.61]

Atir, a cleaner at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "They provide shared accommodation which doesn’t go so well because we are sharing six people in a room."[2.60] Chuki, working as a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai told researchers, "I am in a shared room with five more colleagues from other nationalities making it so difficult to cope as each individual comes with their character and attitude."[2.61]

After the outbreak of COVID-19, the confined accommodation significantly increased workers’ risk of catching the coronavirus and many of the interviewees expressed their frustration that their employers did not reduce the number of people sharing rooms. Firyali, a South African security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai told researchers, "It was really scary, since most staff live together, sharing about 10 persons in a room...it was unbearable, we saw many infections and even deaths."[2.62] Hiari, a woman security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "There was not much change during the pandemic as still I shared the accommodation with five other ladies, making it difficult to practice social distancing."[2.63] Sabir, an Indian security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said "... when COVID-19 started to spread, it was so difficult to maintain the social distancing and more staff got the infection. The employer didn’t take any action to lessen the number of people in an apartment and they didn’t even provide the PPE (personal protection equipment) and sanitizers in the accommodation."[2.64]

The Worker Welfare Assurance Standards stipulates that no more than eight people can share one bedroom and that each person must have at least four - square meters of space in the bedroom.[2.65] It is not clear whether the migrant workers interviewed for this research were provided with the minimum amount of space required under the Worker Welfare Policy, but at least one worker was sharing with more than eight people in violation of the regulations.

As indicated above, there were also issues with some companies not taking adequate measures to protect their staff from infection, particularly in relation to the provision of free masks. Gheche, working in hospitality at Expo 2020 Dubai told Equidem, "They only provided masks to those who were going to work, those who were in the accommodation were forced to buy masks from outside making it not accessible."[2.66] Irfan, who works for a construction company at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "They were selling the masks in the beginning."[2.67]

Chuki , a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "The employer only provided masks at work and not in the accommodation."[2.68] More generally, some interviewees reported work related stress[2.69] and noted that their employers were reluctant to recognise when people were ill and give them time off work. Fadhili, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "The working atmosphere is little bit stressful because UAE police and CIDs are working along with us. So, we have much work pressure to improve our job quality."[2.70]

Sabir, an Indian security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said "... the work stress was high when I moved to Expo 2020 Dubai. I didn’t get adequate rest time and I felt more exhausted." [2.71]

Irfan , a construction worker at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "They only give sick leave when one collapses on the site, they don’t take it seriously."[2.72] Gheche, working in hospitality at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "Whenever I am sick my manager thinks I am faking the sickness, there is no trust."[2.73]

Several interviewees also complained that the food they received as part of their employment package did not provide a healthy and balanced diet. Raz, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai told Equidem, "The company started to give food very recently (instead of the 350 AED personal allowance (US$95)) and the quality is not so good."[2.74] Hiari, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "They provided food which wasn’t nutritious. It was the same every day and full of spice which didn’t accommodate most of us who don’t eat spicy foods."[2.75]

2.6 Treat employees equally and without discrimination and do not tolerate harassment or abuse of any kind

In September 2019, the Government amended the labour law to prohibit discrimination which prejudices equal opportunities in employment, equal access to jobs and continuity of employment. Unfortunately, this provision does not specify what types of discrimination are prohibited and does not meet the concerns which have been repeatedly raised by the ILO. In both 2017 and 2021, the ILO Committee of Experts urged the UAE Government to:

... take the necessary steps to ensure that the amendments to Federal Law No. 8 of 1980 on the regulation of labour relations include a specific provision defining and explicitly prohibiting both direct and indirect discrimination on all the grounds set out in Article 1(1)(a) of the Convention covering all workers, including non-nationals, and all aspects of employment and occupation[2.76]

This gap in the legal protection has left migrant workers vulnerable to discrimination. In 2021, the U.S. State Department highlighted that discrimination against migrants was widespread in the UAE:

Societal discrimination against non-citizens was prevalent and occurred in most areas of daily life, including employment, education, housing, social interaction, and health care.[2.77]

More than a third of the migrant workers interviewed for this research (37%) stated that there was discrimination and/or bullying in the workplace and several gave examples of their direct experience of this. Fadhili, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai told Equidem, "My expectation was high when I came to Dubai, I thought these people will accept me for who I am, but as a migrant and being an African I have gone through many bad experiences. I have been bullied based on my race. I have experienced that employees are not treated by the management equally. I am a first-class degree holder in my country and I have good work experience, (but) the guy who had less qualification and experience than me got a good position."[2.78] Sabir, an Indian security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "...when I was new in this company I was bullied by my senior colleagues. But it was not beyond the limit. I heard that such things are routinely happening with the new joiners."[2.79] Hiari, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai told Equidem "... team leaders and supervisors from our company, the Dubai police and other direct staffs of Expo 2020 Dubai are there to control us. ... Even when we are doing the same work, all those except the nationals are considered as second category. We are getting less salary for the same work and the other work related benefits are also less. I experienced being bullied ... by senior staff."[2.80]

Equidem also recorded incidents of discriminatory practices in relation to salaries for nationals and migrant workers amongst those working on the Expo in research carried out in 2020. For example, a security guard from Nepal stated that:"While working as a visa service agent, the locals there got 16,000 AED ($4,356). But when I sat in the same chair, did the same job, I got 800 AED ($218)."[2.81]

Many of the interviewees noted that there was discrimination based on nationality and/or race which favoured Emirati nationals and Europeans and disadvantaged Asians and Africans. This was particularly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, when migrant workers from Asia and Africa were disproportionately affected by redundancies, pay cuts and increased working hours. Tahoor, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai told Equidem, "There is discrimination in the workplace on the basis of nationality even if it is not so visible. The UAE nationals have all the facilities and salaries, and the deduction of salaries did not affect the UAE citizens."[2.82] Wamai, works for a factory at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "... you could hear some staff saying they’re still getting full salary while others getting only 50%, discrimination was felt just because of racism..."[2.83] Irfan, a construction worker at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "Yes, they discriminate a lot when it comes to dividing work, the Asians are given the heavy work and less pay while the Europeans and Arabs are given lighter roles with lots of income... The Asians were the first to lose their jobs which they work so hard for..."[2.84]

Hiari, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai told researchers, "There is a lot of discrimination in terms of nationalities. Whites and Arabs are given greater opportunities ... Africans and Asians were the first ones to lose their jobs."[2.85] Gheche, working in hospitality at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "There is a lot of discrimination amongst the nationalities at work. I witnessed a lot of discrimination, especially dark-skinned employees who didn’t have anyone to speak on their behalf when the company was looking to fire staff. Some of the workers were given redundancy but especially among the Africans, they were given redundancy without pay."[2.86]

As noted above, Resolution No. 279 (2020) was introduced at the start of the pandemic and permits companies to reduce migrant workers’ wages temporarily or permanently, with the agreement of the employee. This practice is clearly discriminatory as it only applies to migrant workers and it allows companies to implement a prejudicial policy and justify this by arguing that they are operating in full compliance with the UAE’s labour laws.

Furthermore, the provisions brought in under Resolution No.279 do not appear to have been withdrawn or amended,[2.87] even though the force majeure conditions that justified them no longer apply (90% of the UAE’s population is fully vaccinated – the highest percentage in the world).[2.88]

2.7 Provide access to grievance mechanisms and remediation and allow employees freedom to exercise their in-country legal rights without fear of reprisal

The UAE Government has taken steps to try and ensure that migrant workers are aware of their employment rights in the UAE and that they can seek redress for issues they encounter in the workplace. These measures include:

- A “Know Your Rights” campaign, which provides migrant workers arriving at Dubai International Airport with information pamphlets in multiple languages.[2.89]

- Requiring companies involved in Expo 2020 Dubai to deliver induction programmes for workers to raise awareness of their rights.[2.90]

- Providing orientation on UAE labour laws and regulations to low-skilled labourers through its 34 Tawjeeh Centers.[2.91]

- Providing a 24-hour toll-free number through which migrant workers can check the status of their applications, ask questions or file complaints.[2.92]

Despite these initiatives and the Worker Welfare Assurance Standards requirement that workers should have materials distributed to them for reference after their orientation training, none of the migrant workers interviewed for this research received an information pamphlet on their rights, either at Dubai airport or from their employer or any other source.[2.93]

While companies generally did provide training for new employees, respondents highlighted that this focussed on explaining their responsibilities rather than their rights. Raz,a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "Actually, I am not so sure about my rights as an employee. I have only limited knowledge about the labour law in UAE.... the company will not take any initiative to educate their employees about their rights."[2.94] Fadhili, a security guard Expo 2020 Dubai said, "I had a training session from my employer as I was going to be a part of the international Expo. During that time, I got instructions about my responsibilities, but no one talked about my rights as an employee."[2.95] Jwala, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai told Equidem, "I have been working in UAE for 15 years and none of my employers has given any information about my rights as an employee."[2.96] Hamza, a Pakistani security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "I didn’t receive any direction from my employer regarding my rights, but as a part of my training with my employer, they informed me about my duties and responsibilities at the work place."[2.97] Muluk,an Indian security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "I didn’t receive any documents which explains about my right as an employee from the government side or from the employer."[2.98]

However, one respondent did speak positively about an information session they attended at one of the Tawjeeh Centres. Rinjin, a Nepali security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "I got some information through the contract paper. Other than that, the UAE government provides important information about rights of workers through Tawjeeh Center. I attended this one-hour session."[2.99]

The Expo Dubai Committee, the body within Expo Dubai 2020 responsible for organising the event and overseeing worker protections, has stated that it meets all the main Expo contractors at bi-monthly Worker Welfare Forums and that:

All our contractors are obliged to hold regular Worker Welfare Committees with worker-elected representatives, during which members can raise issues and concerns. These must be held at a minimum of every two months. In 2018 we rolled out the Expo 2020 Dubai Worker Hotline – a free phone number available to all those working on the Expo site in eight languages, triaged by experienced call handlers. We have also launched Worker Connect, an app containing information on legal rights that all workers can access from their mobile phones.[2.100]

However, 90% of the migrant workers interviewed for this research said they were not told about either the Worker Welfare Committees, the Worker Connect app or the Expo 2020 Dubai hotline. Sabir, who works for Fist Security Group at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "Our company had partnership with Expo 2020 Dubai very recently and those who got selected for the Expo got special training ... But we didn’t get any information about Welfare Committees and other hotline sites in any session."[2.101] Muluk, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai told Equidem, "I have been working with Expo 2020 Dubai for two months and none of us have been told about any Welfare Committees or Worker Connect app related to Expo 2020 Dubai."[2.102]

Of the three migrant workers who were aware of at least one of the above mechanisms for addressing issues at work, one indicated that his company was following a good practice model in terms of informing employees about how they can raise concerns. Mankaji, a housekeeping supervisor at Expo 2020 Dubai told Equidem, "I know about the Worker Welfare (Committee), hotline and security at Expo 2020 Dubai. We were given a training before joining. We also get occasional reminder/ information from the supervisor."[2.103]

Migrant workers who need to sort out a work-related problem can use the Tawa-Fouq (reconciliation) centres. These centres were launched specifically for migrant workers by the MOHRE in 2018 to perform a preliminary mediation role to resolve labour disputes and make recommendations to the MOHRE.[2.104] In addition, all private-sector employees can file complaints directly with the MOHRE, which by law acts as mediator between the parties. If a dispute remains unresolved, employees can then file the case in the labour court system, which forwards disputes to a conciliation council. Administrative remedies are available for labour complaints, and the authorities applied them to resolve issues such as delayed wage payments and unpaid overtime.[2.105]

It is not possible to properly evaluate these redress mechanisms as the UAE Government does not provide data on the number of people using these procedures, the nature of the complaint or how it was resolved. The U.S. State Department drew attention to this issue in 2021 and noted that the Government has not reported the number of complaints of unpaid wages it investigated through its dispute resolution process for 13 consecutive years.[2.106] Similarly, the ILO recently called on the Government to:

... provide statistical information on the number of migrant workers who had recourse to the complaints mechanisms and the outcomes.[2.107]

Furthermore, the UAE Government does not allow independent organisations to review the operation of its dispute resolution procedures or its labour courts. This is reflected in the fact that it has not allowed United Nations’ experts access to the country to review its compliance with international standards since 2014, when a UN Special Rapporteur issued a report criticising a lack of judicial independence.[2.108]

However, even without this data, it is difficult to consider that this system provides a fair and effective redress mechanism for migrant workers suffering violations of their labour rights as the power relationship between the employer and the employee is so unbalanced. The UAE does not permit migrant workers to freely associate, organise, form or join an independent union, bargain collectively or strike.[2.109] Nor can they access independent and professional advice and representation to assist them in taking forward a complaint. This makes it extremely difficult for an employee to successfully challenge a decision taken by their employer or the Government.

Furthermore, the threat of dismissal, deportation, the non-renewal of a contract or simply that they will receive less favourable treatment or opportunities at work, is sufficient to discourage most migrant workers from expressing a work-related grievance. This is reflected in the research findings, as none of the interviewees reported or tried to address any of the problems they had at work. Even those who described facing bullying, discrimination and other serious labour rights violations were unwilling to file a complaint because they feared they would be subject to reprisals and/or that it would not achieve anything :

Raz, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai told researchers "... I am afraid to make a complaint. I am worried that it may affect my future in UAE."[2.110] Fadhili, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "I have never raised any complaint on the bullying, because I know there will not be any change if I make any complaint. I want to continue my job as I have some financial problems."[2.111] Sabir, a security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "I was aware about such situations (bullying) from my friends and it was necessary for me to stick on this job so I keep on handling things in a positive way. Also, I was little bit afraid to raise complainant."[2.112] Tahoor, a Pakistani security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "All the companies in UAE are giving priorities for their citizens so there is no use for complaining."[2.113]

The ILO has recently drawn attention to this issue and called on the Government to:

... take measures to strengthen the capacity of migrant workers to enable them, in practice, to approach the competent authorities and seek redress in the event of a violation of their rights or abuses, without fear of retaliation.[2.114]

For those workers who do try and remedy a problem at work, the emphasis on resolving the dispute amicably and the power imbalance in the system makes it difficult for a worker to reject a proposal from the MOHRE even if they felt it did not adequately redress an injustice they had suffered. However, the onus for identifying and challenging labour rights violations does not only rest on employees. Both the UAE Government and the employer have a responsibility to ensure that all those involved in Expo 2020 Dubai are in full compliance with their contractual obligations and UAE labour legislation.

Expo 2020 Dubai authorities stipulate that all employers must: allocate sufficient resources to ensure that standards are being met; conduct periodic audits and reviews of performance, including by subcontractors; and investigate and report incidents relating to breaches of these standards.[2.115] This is reinforced in the Worker Welfare Assurance Standards, which require contractors to monitor accommodation facilities and employment practices; undertake regular inspections to ensure that their own organisations and their subcontractors are in compliance with the Standards; and implement corrective action where required. Evidence provided by migrant workers who participated in this research indicates that some companies are not properly discharging these obligations or performing their due diligence adequately, and that others are directly involved in labour rights violations.

The Government monitors and enforces compliance with the UAE’s labour laws through a labour inspection system which is made up of some 700 inspectors.[2.116]. It reported that it conducted 280,728 labour inspections in 2020[2.117] and documented 1,146 cases of labour violations. Of these, 1,144 cases were of late payment of wages and involved 80,633 migrant workers. The two other cases were linked to illegal salary deductions and a failure to calculate overtime pay.[2.118] In all the above cases fines were issued, but it does not appear that any were referred for further investigation to see if additional charges should be initiated (e.g. for forced labour or trafficking offences).

Given the findings from this research and from other reputable sources such as the U.S. State Department and the ILO, it is concerning that the labour inspectors did not identify a single case in which a worker was charged recruitment fees; had their documents confiscated; or was subject to bullying or discrimination. It is equally worrying that only two cases relating to salary deductions and unpaid overtime were detected in an entire year. This indicates that the UAE’s labour inspection system is not sufficiently proactive in identifying cases of non-compliance with the labour laws.

2.8 Address structural barriers to forced labour prevention

In 2015, the UAE Government enacted three Ministerial Decrees to give workers more flexibility to change jobs and reduce their vulnerability to forced labour practices, all of which came into force on 1 January 2016. They were:

- Ministerial Decree No. 764 on Ministry of Labour-approved Standard Employment Contracts;

- Ministerial Decree No. 765 on Rules and Conditions for the Termination of Employment Relations;

- Ministerial Decree No. 766 on Rules and Conditions for Granting a New Work Permit to a Worker whose Labour Relations with an Employer has Ended.[2.119]

Under Ministerial Decree No. 765, where there is a fixed-term contract of two years, either party can terminate the contract. This allows a worker to leave their job providing they complete a notice period of up to three months and that the other requirements of the regulations are observed.

Interviewees generally confirmed that they were able to leave their jobs if they completed the notice period in their contracts, which was typically 45 days. Muluk, an Indian security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai said, "The employee should give a notification period of 45 days and then they can leave the company with their end of service benefits and the company will give the NOC (No Objection Certificate) for another job."[2.120] Tahoor, a Pakistani Security guard at Expo 2020 Dubai told Equidem, "But it should be according to the company policy. There is notification period of 45 days and only then the employee will get their end of service benefits."[2.121]